|

MEETING #1683

4:00 P.M.

April 24, 2003

A Family Legend

by Halcott G. Grant

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public

Library

SYNOPSIS

This paper traces the early history of

a young Scotsman named John Paul, born in Arbigland, Scotland, who went to sea,

apprenticed to a sea captain in 1761 at the tender age of 13. During the next 12 years on

several ships he matured and became captain of square riggers trading between Scotland and

the Colonies. This period of his life came to an abrupt end in Tobago in the West Indies

in 1773 when he was confronted by a mutinous crewman, resulting in John Paul running him

through with his sword, killing him. This necessitated an escape from the island to avoid

being jailed or worse. He then went incognito for almost two years, hoping to return later

to clear his name before an Admiralty Court. There is no written record of his whereabouts

or activities for the next 20 months or so.

Later that year according to the family legend and the official North

Carolina position, John Paul was befriended by the brothers, Willie (pronounced Wylie) and

Alan Jones, prominent planters and politicians in Halifax, North Carolina. Their

friendship develops, and when he made the decision to offer his naval expertise to the

fledgling United States, John Paul asked the brothers to allow him to assume their name “Jones” as his surname, and that he would make them proud of it. They agreed and

the rest of his story is history.

The prominent Naval Historian, Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, in his

definitive biography “John Paul Jones, A Sailor’s Biography” printed in

1959, relegates this theory to his appendices and states that he doesn’t think it

true.

Evidence to support the oral history of the “North Carolina

Position” and the family tradition is contained in two books printed after Morison’s

biography: Elizabeth Cotton’s “The John Paul Jones Willie Jones Tradition,”

A Defense of the North Carolina Position, printed in 1966 and “The Land and the

People” by Margaret Green Devereux, a direct descendant of Alan Jones, printed in

1974. Historians don’t seem to want to accept historical data unless supported by

written evidence. This paper questions why oral history, telling the same story from

several sources, can’t be given the same weight in reconstructing the past.

The paper ends with a short description of the momentous Naval battle

between the United States’s Bonhomme Richard and Britain’s Serapis, during

which John Paul Jones cried when challenged “I have not yet begun to fight!” during his victory over his stronger foe.

A Family Legend

One day in 1774, in Halifax Town, North Carolina, Willie (pronounced Wylie) Jones was

walking down the street and encountered a lonely and depressed stranger resting on a bench

outside a tavern. Willie asked, “What is your name” the reply was “I have

none”, and “Where is your home”, again the reply was “I have

none”. So starts a relationship that this young man and Willie and his brother Allen

had, which was to last about two years, but which would cause controversy and historical

uncertainty up to the present day.

Who was this young man,

and who are Willie and Allen Jones?

First of all, I want to tell you about the young man. His name was John Paul. He was

born in Arbigland, Scotland on July 6, 1747. His father was a gardener for a landowner,

William Craik, and spent an uneventful childhood on the banks of the Solway Firth on the

west coast of Scotland, at the border of England. In those days, kids didn’t get much

education or social training so they pursued whatever direction seemed possible to them as

they grew up. Since he was on the banks of the Solway, and was around ships and seamen, in

1761 he went away to sea at the tender age of 13. Having completed the schooling available

to him at the parochial school and having signed articles of apprenticeship for seven

years, he left receiving almost no pay but learning the mariner’s profession.

His first ship was the brig Friendship, a cargo vessel of 179 tons which sailed between

Whitehaven, Scotland and Fredericksburg, Virginia, one round trip yearly. He was able to

make contact with, and to visit his brother , a tailor in Fredericksburg, Virginia during

this period which lasted only two years, as the 7 Years War in Europe was over and trade

was drying up. In 1764, the owner of the Friendship went broke and sold it, releasing John

Paul from his apprenticeship obligation. According to Samuel Eliot Morrison in his

Biography, “John Paul Jones” he then signed on to the slave trade and at the age

of 17 became the third mate of the King George, a “blackbirder” out of

Whitehaven. After two years on the King George he became chief mate of the slaver Two

Friends of Kingston, Jamaica. This was a small vessel of 30 tons not over 50 feet long

with a crew of six men and officers and carrying 77 negros from Africa. One can imagine

the horror of that voyage and how many of the cargo survived. At the end of one round

trip, John Paul obtained his discharge, leaving “that abominable trade”.

At this point he was in Kingston and was lucky enough to run into Samuel McAdam of

Kirkcudbright, Scotland, (on the Firth of Solway), the part owner and Master of the brig

John of Liverpool. John Paul, coming from the same area and being a personable young man,

made friends with him and was offered a free passage home, which he happily accepted. It

proved to be an eventful voyage, as his new friend, Samuel McAdam and his mate died during

the voyage of “a fever” and John Paul jumped into the breech bringing the ship

safely home to Kirkcudbright. Naturally this made the other owners very happy and they

awarded him command of John, and as such, he made at least two round trip voyages to the

West Indies.

The first voyage was relatively routine, carrying salt provisions and consumer goods to

Jamaica to trade for local products for transportation back to Kirkcudbright. As a matter

of interest, the cargo he carried back on this first voyage consisted of 49 hogsheads and

6 casks of sugar, 156 puncheons of rum, 44 bags of pimentos, 6 bags of cotton, 75 mahogany

planks, and 2 ½ tons of logwood & fustick, the dyewoods that the Jamaicans cut at

Campeche. Logwood was used to make blue and black dyes and fustick for yellows. He got

back to Kirkcudbright by the end of August 1769, too late to return before the next

spring.

His second voyage took until the end of 1770 for his return to Kirkcudbright. His cargo

was similar, but the voyage itself was eventful. John Paul, as he matured, developed an

explosive temper which got him into a serious scrape. Mungo Maxwell, the son of a

prominent buisnessman in Kirkcudbright was hired as the ships carpenter by the owners and

turned out to be incompetent and disobedient. Midway into the journey to Jamiaca John Paul

had had enough of Mungo and strung him up in the rigging and had him lashed with the

cat-o’-nine-tails. When the ship arrived in Jamiaca, Mungo complained to the

vice-admiralty court. When the court heard the evidence and examined Mungo’s torso,

they declared that his wounds were “neither mortal nor dangerous” and dismissed

the complaint as frivolous. Mungo then left for home on another ship, came down with a

fever and died at sea. When Mungo’s father heard about his son’s death, he

believed that the death was caused by the flogging and brought Captain Paul to court

saying his son

“was most unmercifully, by the said John Paul, with a great cudgel or batton,

bled, bruized and wounded upon his back and other parts of his body, and of which wounds

and bruises he soon afterward died on board the Barcelona Packet of London”.

John Paul then found it necessary to convince the court that he could prove his

innocence and would stand trial when he was able to gather the evidence. He did so and was

subsequently cleared of all charges. In spite of this incident, it seems that he had

conducted himself so well in his commercial dealings as master of the John that he had the

respect of the community and the ship’s owners. He was initiated into the Masons

Lodge of Kirkcudbright that fall of 1770, a step up for him that was to be to his

advantage for the rest of his life. Masonry was highly regarded, both in England and the

Colonies, and provided John Paul access to the gentry and even nobility of the various

cities he would visit during his lifetime. He was not shy about taking this advantage.

In early 1771 the John was sold and Captain Paul was given an honorable discharge with

high recommendations. There doesn’t seem to be any record of our hero’s

activities other than he was in Tobago in the spring of 1772 and obtained documents

clearing his name as mentioned previously. Because his reputation had grown he managed to

be made Master of a large square rigger, the Betsy, and probably a part owner in the fall

of 1772. Using the trading experience he got as Master of the John and the continuing

experience of being master of a large square rigged ship, he established partnerships with

Tobago people resulting in making it a very successful ship. There is evidence that by

1773 he was closing in on his dream of becoming rich enough to give up the sea, find a

wife and become a planter in Virginia. These dreams came from his early voyages when he

was able to observe how the gentry and landowners lived.

These dreams all came to an end at the end of his second voyage in the Betsy when the

ship was in Scarborough, Tobago. He was in the process of trying to purchase a cargo for

his return trip to England, and to make sure he had enough cash to make the purchases, he

unwisely refused to advance wages to his crew, telling them they wouldn’t be paid

until they got to England. Many of the crew were locals to Scarborough, and they wanted

some pay to spend with their friends and relatives ashore. The details that are known of

what happened then come from a letter John Paul wrote to Benjamin Franklin in 1778.

One of the crew, who was a troublemaker on the outbound voyage, stirred up the rest of

the crew and made a demand that they be paid a once. John Paul attempted to appease them,

by offering them clothing but the ringleader refused and threatened to lower a boat and go

ashore without leave. Captain Paul tried to stop them, but was threatened by the very

large and powerful seaman and was forced to take refuge in the captain’s cabin.. The

skipper , not to be faced down by this totally unruly crewman, took his sword from the

cabin table and stormed forth, hoping to intimidate him, but it had the opposite result.

His opponent let out a mighty roar and charged him, brandishing a club. Having to retreat,

The skipper backed up until his heel encountered the sill of an open hatchway. Not being

able to retreat any further, he had no choice but to defend himself and ran the seaman

through with his sword just a the club was descending toward his head. The vicious crewman

fell dead at his feet, thus stopping the mutiny, but creating a huge problem for himself.

Although he had defeated the mutiny attempt, he felt that he should turn himself in to

the authorities because of his causing the seaman’s demise. He immediately went

ashore and met with the justice of the peace. He was informed that in all probability, if

an Admiralty Court were to hear his case, he would be found to have acted within his

authority and that turning himself in wasn’t necessary. However, there was no

authority in Tobago to try an Admiralty case and his friends in Tobago felt he

wouldn’t stand a chance in a civil court, so he was persuaded to flee the island at

once. He thereupon crossed to the other side of the island on horseback to a bay in which

there was a vessel on which he got away. He left all his possessions, excepting 50 pounds

which he took with him, in the hands of his partner Archibald Stewart and his agent

Stewart Mawey.

Admiral Morrison correctly points out that it seems strange that a man whose

personality was such that he would seek solutions to problems in the most direct way would

choose to flee rather than fight for his rights, particularly in those times when the

skipper of a vessel had almost absolute power over his crew, and the courts almost always

backed the Captain. It must have been that the guy he ran through was a local Tobago man

with a large family who stirred things up to the point that John’s friends felt that

he was in danger, so urged him to make his exit, which he did.

Here the written history of what happened to John Paul peters out for a period of

almost 2 years. Morison conjectures that he left the Islands, changing his name to Jones,

possibly because it is a patronymic, or the son of John, or possibly because it was, then

as now, common enough that it would not stand out. It probably was in his mind to

disappear until such time that he was able to return to Tobago to clear his name. Morison

was able to identify that John Paul, now known as Paul Jones, spent some time in

Philadelphia and Virginia, but with no details filling in the twenty months during which

there is so little written detail of his activities. The beginning of this period was

sometime in the last 3 months of 1773. Morison admits that his movements are an almost

complete mystery historically, and that trying to reconstruct them is like trying to solve

a picture puzzle with 90% of the pieces missing.

He relates that John Paul escaped Tobago from a harbor across the island from

Scarborough called Courland Bay, which was a port of call for the British Mail Packets

which cruised the Islands. One of these packets may well have been available to him,

giving him transportation to Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, Antigua or Jamaica where

further transportation would have been available to the Continent. Admiral Morison

continues that there was no doubt that John Paul then went “incog” as he said as

much in his letter to Ben Franklin written in 1779 in order to avoid prosecution for the

event in Tobago. Morison next has, now, John Jones in Virginia, where John’s brother,

William Paul, a tailor in Fredericksburg, died in 1774. William left all his property to

his sister and her children in Scotland, not to his estranged wife, or to his brother John

according to the will of record.

Morison conjectures that the courts probably let John live in his brothers house while

the estate was being settled. He then suggests that John befriended a Dr. John K. Read,

probably through the Masonic Lodge, and that through him he met Joseph Hewes, a leading

Shipbuilder, merchant and politician of Edenton, North Carolina. This, in turn, has John

Jones and the Doctor spending many sentimental hours together at “The Grove”, an

adjoining estate owned by a family named Crenshaw. Research done by others dispute this,

as there is no record of any estate named “The Grove” in Virginia. He also has

John in a romance with Dorothea Dandridge, who subsequently married Patrick Henry, as she

was mentioned in later correspondence between the Doctor and John Paul Jones. As I said

before, during this period of less than two years, Admiral Morison continuously uses

modifying phrases such as “may have” or “reasonable to assume” since

there is no paper trail following his adventures during this time.

To provide an alternative possibility as to how this time was spent, I will use as

reference two books, the first published by Heritage Printers of Charlotte, N.C. by

Elizabeth H. Cotton entitled “The John Paul Jones Willie Jones Tradition,” and

the other “The Land and the People” by my aunt Margaret Green Devereux,

published by Vantage Press. Both were published after Admiral Morison’s “John

Paul Jones, A Sailor’s Biography” went to press in 1959. They provide a

different take on how John Paul acquired and kept the surname ”Jones”. Elizabeth

Cotton was a patriotic member of a prominent North Carolina family, wife of a

distinguished naval officer and a long time curator of manuscripts in the Southern

Historical Collection at Chapel Hill. An avid supporter of the so called “North

Carolina Tradition”, she researched in great detail all aspects of the controversy

created because all Jones family records were lost in a fire which destroyed Willie’s

daughter’s house and everything in it, including correspondence of both Allen and

Willie Jones including a portrait of John Paul Jones, sent by him to Mrs. Allen Jones. She

had as supporters of her point of view Colonel Cadwallader Jones, author of “A

Genealogical History” of the Jones family, published in 1899, Secretary of the Navy

under Woodrow Wilson, Josephs Daniels and Captain H. A. Baldridge, Director of the Naval

Academy Museum at Annapolis. Both of the latter gentlemen’s correspondence is

included in Elizabeth Cotton’s volume, signing on to the premise put forward.

Margaret Devereux, my mother’s sister, with the help of her brother, Halcott

Green, wrote “The Land and the People”, a volume created for the family, and

which includes several chapters on the Jones. Much of the information comes from my

grandfather, Halcott Pride Green, who compiled all the data available to him, and perhaps

could have written the book himself.

Who were Willie and Allen Jones?

The Jones brothers were the great, great grandsons of Robin Jones, my Grandfather, nine

generations or so back, born in Wales in 1640 arriving in Norfolk, Virginia in 1663. His

grandson, Robert, became a planter, and was a prominent member of the educated few who was

most influential in the early development of North Carolina. As the wilderness gave way to

settlement, Indian Tribes were displaced and vast tracts of land were acquired. Robin,

educated in England at Eaton College, moved his family from Sussex County , sometime

between 1750 and 1753 to Northampton County in North Carolina on the banks of the Roanoke

River, and built his house “The Castle”. He represented the County in the North

Carolina assembly from 1754 to 1761. In that year he was appointed Attorney General for

the Crown for the Province of North Carolina. He was also Agent for Lord Granville, the

sole member of the North Carolina Proprietary Government who retained his large holdings

of land in the Province. Through these positions and being an astute businessman, he was

able to acquire large tracts of land, becoming in a few years perhaps the largest landed

proprietor on the Roanoke and maybe the largest in the Province. He was again elected to

the Assembly in 1766 when he was 49 years old, but because of his death in October that

year, did not serve.

He sent his two sons to England for their education, both going to Eaton College as he

had. Allen, from whom I am descended, the eldest, returned after school, but Willie

remained, continuing his studies at Eaton, and then traveling through Europe. During this

time he observed and learned about how the people lived and were ruled in Europe,

particularly the way the common folk were mistreated by Royalty, although there are no

records telling us exactly what his itinerary was. He returned home a far more cultivated

and mature man than he was when he left. Allen, meanwhile returned home in 1753 and became

a successful planter on the family property just outside Halifax. In 1766, Robin died and

chose his two sons to be his executors along with his friend Joseph John Alston. His vast

lands were divvied up between the two boys. Allen built his estate “Mt. Gallant”

across the river in Northampton County on his inherited property, while Willie built his

estate “The Grove” in Halifax County, probably between 1772 and 1775 using many

of the architectural details from his father’s house “The Castle”. Allen

and Willie were successful planters in the area and after their marriages, among the

social leaders.

Willie was, while still a bachelor. a free wheeling sportsman who bred and raced horses

and was known to bet large sums. His estate “The Grove” had in it the first

known bow window anywhere in it’s great room through which he could watch the horses

race on his own race track out back. He married Mary Montfort in 1776 and had several

children. Their house was known for it’s hospitality and they were known for their

gathering of the poor and bereft. An unusual trait in those days.

During this period of the latter 60’s and into the 70’s the stirrings of

rebellion were spreading and the brothers were caught up in the dreams of self rule,

unencumbered with the demands of the far off Crown. Willie’s politics and ideology

were developing quite differently from his brother who was a conservative and believed

that only the educated men of proven ability and experience with responsibility in owning

property should be leaders. He, Willie, was of the opinion that the common people should

have a say in how society should be run and fought successfully for the Bill of Rights in

North Carolina, and in fact has been given credit for being the creator of the North

Carolina Constitution.

Allan, who became a General in the North Carolina Militia during the Revolution,

differed from Willie on the subject of the return of property to the Tories which had been

summarily confiscated, where Willie thought it should be disseminated to the

“Have-nots”.

Willie felt that paper money should be issued to help the common man, whereas Allen was

adamant that money should not be printed without sufficient guarantee to back it up.

Allan, as an elected member of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia approved

the adoption of the Constitution of the United States of America by North Carolina whereas

Willie disagreed, and in fact refused to succeed his brother when Allen was too sick to

continue after serving for a year as a delegate in 1779 and 1780. The Constitution was

finally adopted by North Carolina in Hillsborough in 1789, with the brothers on opposite

sides.

They were close personally and socially until a rift occurred between them at some

point during the 1780’s or the 1790’s which split them and their families apart.

The exact cause doesn’t survive, but we can surmise that the reason was political in

those days when political thought was the overwhelming subject in the drawing rooms

throughout the colonies or the fledging United States.

So, this is a brief description of the brothers and their position in the countryside

where the sad young man was approached in front of a tavern in Halifax in 1773. Willie,

one of the most powerful men in the colony, known for his sympathy and compassion for the

common man, with an intellect equaled by few others, engaged him in a labored

conversation:

“What is your name?”

“I have none,” the young man said.

“Where is your home?”

“I have none,” again was the reply.

Willie engaged him in kindly conversation, and took him home to “The

Grove” where he remained for a year or more, leaving Halifax for several months, then

returning again. Some of those months were spent at “Mount Gallant”, the home of

Alan Jones, and in fact he recovered from a bout of typhoid fever there under the care of

Allan’s second wife, Rebecca during the first months. A close relationship developed

between the brothers and the sailor. In the meantime, the winds of war were developing and

John Paul, having adopted the ways of the aristocratic Joneses, and being wholly

sympathetic to the revolutionary positions of the brothers, expressed a desire to put his

expertise as a ships captain at the disposal of the colonies in the looming showdown with

the British.

Both Alan and Willie gave their full support to his desire to go back to sea, and the

following scene has been described with essentially the same details through several

separate family branches via oral history, backed up by written statements of family

members when Admiral Morison’s total rejection of the validity of North

Carolina’s and the Jones’ family claim as to how the name change occurred. John

Paul expressed his desire to go back to sea and Willie offered him money to tide him over,

but was refused , so instead offered him his sword, which was accepted with gratitude.

John Paul then asked of the brothers that they allow him to adopt the name

“Jones” as his new surname, and that he would make them proud of it. Willey and

Alan, flattered, gave him permission and so John Paul became John Paul Jones.

Willie introduced him to Congress through Joseph Hewes who had been appointed by

Congress a member of the Naval Committee, who caused him to be appointed a first

lieutenant in the American Navy on December 22, 1775. His subsequent career in the Navy is

history, the most famous incident, of course, being his great naval victory in the battle

between his “Bonhomme Richard” and the British Man of War “Serapis” in

view of the English shoreline off Flamborough Head in Yorkshire.

Since there has been no updated biography of John Paul Jones since Admiral

Morison’s “A Sailor’s Biography” which either accepts or rejects the

“North Carolina Tradition”, I would like to address a couple of the principal

reasons that the family, that is the descendents of Willie and Allen Jones, believe that

they are correct in making the claim that his surname is their Jones.

Admiral Morison says, here I quote, that

“the tradition even acquired properties. In the Naval Academy at the Museum at

Annapolis, is a broad sword presented by Rear Admiral R. F. Nicholson, U. S. N., in 1924,

which to quote the museum’s catalog at that time ‘According to tradition was

given by Willie Jones of North Carolina in 1775 to John Paul Jones, used by Jones during

the Revolution and given by him to Theodosia Burr, daughter of Aaron Burr. Later presented

to the Nicholson family. There is no inscription on the sword and John Paul Jones, so far

as evidence exists never even met Theodosia Burr. There is certainly no reason why he

should have given her the sword.”"

Here Elizabeth Cotton refers to the Honorable Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy

in the cabinet of Woodrow Wilson, and Ambassador to Mexico during the administration of

Franklin Roosevelt, and his address to The North Carolina Literary and Historical Society

wherein he traces the history of the sword as follows:

“It is known that the Naval officer (John Paul Jones) presented the sword to Judge

Matthew Davis of South Carolina, who gave it to his intimate friend, Aaron Burr, who gave

it to his daughter Theodosia Alston, who gave it to Mr. Duchachet, of Philadelphia, who in

turn presented it to his nephew, Commodore Somerville Nicholson, father of Admiral

Nicholson to whom it now belongs.”

It is on loan to the Naval Academy Museum where it is on display. This documented

provenance, which corrected the museum catalog, effectively rebuts Morison’s

position.

Morison allows as how John Paul “may have met” Willie somewhere - in Edenton,

the port city at he mouth of the Roanoke River, where he may have gone looking for work at

Hewes & Smith, the enterprise partly owned by Joseph Hewes. It seems this would have

been a strange place for a man, supposedly attempting to be “incog” to go,

because the port would have been full of the kind of people who might recognize him.

Morison continues that the negative evidence against John Paul taking the name as a

compliment to Willie and Allan Jones is overwhelming, basing his conclusions, among

others, as follows:

-

No letters exist. We know that all of the Willie and Allan Jones correspondence were

lost when a fire destroyed Willie’s granddaughter’s house in Virginia in the

late 1860s.

-

John Paul Jones never mentions the Jones brothers in any known correspondence. This is

true, but we should keep in mind that no letters of either Willie or Allan’s survive,

yet family members have stated they remember seeing letters from John Paul to Mrs. Allan

Jones. Admittedly, there is no documentary evidence.

-

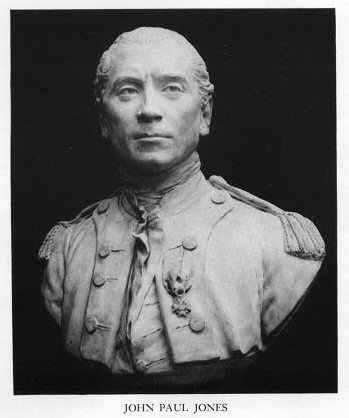

Morison says that John Paul had over a dozen casts of a bust of him by French sculptor

Houdon, and presented them to various American friends, but none to Allan or Willie or any

other North Carolinians. This is true, however John Paul Jones’ diary states that he

only gave them to those who asked for one with the exception of Thomas Jefferson, at the

time the American Minister to France, to whom he was particularly indebted at the time.

Elizabeth Cotton writes in her book that her friend, Mrs. Robert T. Newcomb, a direct

descendant of Willie and Mary Jones, heard her mother relate how her mother, a great

granddaughter of Willie Jones, speak many times of how her grandmother grew up, until she

was 14 years old at “The Grove”, with her Grandmother, Sarah Welsh Jones Burton,

Willie’s daughter. She heard often of letters received by Mrs. Willie Jones from John

Paul Jones. In fact, the famous man sent to little Sarah a gold brooch and a cap of

beautiful French lace. The brooch was always worn on important occasions, when she was

married to Hutchens Burton and to his inauguration as Governor of North Carolina on

December 7, 1825. Elizabeth Cotton has held in her hands the delicate lace and the brooch,

now owned by Mrs. Newcomb, which is small, almost square with a space in the center which

once held a lock of hair, long since gone, that of John Paul Jones. Prior to the

publication of Elizabeth Cotton’s book, this information was not available to anyone.

It was part of the family’s oral history, with the backup of the objects, again

identified by oral history. Would the women of those successive generations consistently

lie about the provenance? It seems most unlikely.

Finally, I want to quote a paragraph from “A Genealogical History” by Colonel

Cadwallader Jones, C.S.A. of Columbia, South Carolina, Grandson of General Allan Jones,

published in 1899, the year of his death. He writes:

“Willie Jones lived at the ‘The Grove’ near Halifax. These old mansions,

grand in their proportions, were the home of abounding hospitality. In connection, I may

mention that when John Paul visited Halifax, then a young sailor and a stranger, he made

the acquaintance of those grand old patriots, Allan and Willie Jones; he a young man but

an old tar, with a bold frank sailor bearing that attracted their attention. He became a

frequent visitor at their houses, where he was always welcome. He soon grew fond of them,

and as a mark of his esteem and admiration he adopter their name saying that ‘if he

lived he would make them proud of it.’ Thus John Paul became John Paul Jones - it was

his fancy. He named his ship Bonhomme Richard in compliment to Benjamin Franklin and his

“Richard’s Almanac” He named himself Jones in compliment to Allan and

Willie Jones. When the first notes of War sounded he obtained letters from these brothers

to Joseph Hewes, member of Congress from North Carolina, and through his influence

received his first commission in the navy. I am the oldest living descendent of General

Allan Jones. I remember my Aunt, Mrs. Willie Jones, who survived her husband many years,

and when a boy I heard these fact spoken of often in both families.”

So, this is the family legend, or perhaps it should be called “a tradition”

which takes exception to what Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, the author of what is

considered the definitive biography of this wonderful character, says about his surname

Jones. I have tried to present some of the arguments in favor of our legend, but run into

the problem that , in spite of oral history, historians have a difficult time putting

their names to statements that cannot be backed up by documentation. The family stands by

tradition and oral history, believing that memories, such as is demonstrated by

Cadwallader Jones, Mrs. Robert Newcomb and others not mentioned in this paper but which

appear in Elizabeth Cotton’s book, are too consistent in detail to dismiss as

unworthy of mention in serious historical dissertations.

John Paul Jones was a giant figure in the Naval History of our country. During his

career he was the first to put onto paper the beginnings of the regulations which regulate

how the Navy operates today. The battle which brought him fame, between his Bonhomme

Richard and the British Serapis is worthy of describing briefly, because it illustrates

what a feisty character he was.

Commodore Jones had, for some weeks, in the summer and early fall of 1779 been cruising

the coasts of England, accompanied by three other ships, one of which, the Alliance, was

captained by a French Captain named Landais, who, because of differing views wanted

nothing more than to see Jones destroyed. The small force had been very successful, taking

a number of prizes and in general, terrorizing the British countryside. In the early

afternoon of the 23rd of September, 1779 as they were sailing north in light winds, they

sighted a fleet of 41 sail approaching Flamborough Head, a convoy from the Baltic escorted

by the British frigate Serapis (44 guns) and the sloop of war Countess of Scarborough (20

guns). The Commodore realized that a long sought opportunity had arrived!

The H.M.S. Serapis was commanded by Captain Richard Pearson RN, was a new

copper-bottomed frigate rated at 44 guns, but with 50; a main battery of 20

eighteen-pounders on a lower gun deck (compared with Richard’s 6); 20 nine-pounders

on an upper covered gun deck (compared with Richard’s 28 twelve-pounders), and 10

six-pounders on the quarterdeck (where Richard had 6 nine-pounders), making the Serapis a

far stronger ship that the Richard.

Upon sighting the Richard, the convoy cracked on sail and headed north to take refuge

under the guns of Scarborough Castle. Serapis changed course to get between the Richard

and the other American ships and the convoy, not flinching at the opportunity to engage a

superior number of ships. Because of light winds, Jones realized that he would have to

take or sink the two escorts in order to get at the convoy. He readied the ship for action

and at 6:00 signaled his ships to action. The Alliance would have none of it and hauled to

sea and his other ship, the Pallas veered off leaving the Richard alone to face the

Serapis. The Pallas redeemed herself later by engaging and taking the Countess of

Scarborough. Jones’ fourth ship, the Vengeance simply sailed around watching.

The battle started with the Serapis and the Richard firing broadsides at each other,

both maneuvering to gain position for additional broadsides. Two of Jones’s

eighteen-pounders exploded and put the others out of commission, killing many gunners and

blowing up part of the deck above. The Commodore realized that he would not prevail in a

gun to gun duel and that he would have to attempt to board and grapple. In the subsequent

maneuvering the two ships collided, Serapis’s bowsprit against the Richard’s

mizzen. At this point, Jones himself lashed the two ships together, and they pirouetted

around and ended up side by side, bow to stern and stern to bow. It was at this moment

that Captain Pearson called out “Has your ship struck?” and Paul Jones made the

immortal reply,

I HAVE NOT YET BEGUN TO FIGHT.

Because the ships were tightly side by side, the continuing cannon fire was effective

in doing great damage to the ships, but less effective in killing the crews, however the

American Marines in the rigging of the Richard were extremely effective with their

musketry and grenades, making the deck of the Serapis a death trap. The battle raged on,

and the Alliance, as mentioned, captained by the not so loyal Landais circled and fired

several broadsides, not at the Serapis, but at the Bonhomme Richard, killing several men

and putting a hole in the hull. This could not have been accidental as all the proper

signals were flying.

The battle continued, Commodore Jones himself manning one of the last nine-pounders,

was begged by one of his sailors to strike, but he cried “no, I will sink, I will

never strike!” At about 10:30, the battle having raged on since 6:30, one of the

marines in the rigging dropped a grenade into an open hatch of the Serapis and ignited a

store of powder killing at least twenty men, and the mainmast of the Serapis began to go.

At this Captain Pearson lost his nerve and struck his colors, thus ending the long ordeal.

Commodore Jones and his crew took over and, believe it or not, Captain Pearson was invited

into Commodore Jones’s cabin for a glass of wine! War was conducted differently in

those days. Two days later the Bonhomme Richard, mortally wounded, sank.

His fame was instantaneous, a Sword of gold presented by King Louis XVI, letters of

congratulation from Franklin and Washington, and from Congress a vote of thanks and a gold

medal. He subsequently fought as a mercenary for Catherine the Great of Russia and ended

his days in Paris, all but forgotten by the country he so bravely served. He died on July

18, 1792 and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

It wasn’t until 1899 that through the efforts of General Horace Porter, Ambassador

to France, a search for his unmarked grave was started. It wasn’t until 1905 that his

grave, finally identified, was opened and his body exhumed and identified. President

Theodore Roosevelt sent four cruisers to bring his body home, knowing the propaganda value

for the Navy. It was placed in a temporary vault in Annapolis where it remained until it

was interred in the crypt of the chapel of the Naval Academy in Annapolis Maryland.

Congress, after all those years, finally appropriated funds for a marble sarcophagus with

surroundings reminiscent of Napoleon’s tomb. An appropriate ending for one of our

Country’s most enduring heroes.

A Little About the Author of this Paper,

Halcott Green Grant

Born in

Columbia, South Carolina in 1927, and moved with his family to Weston, Massachusetts in

1930.

Attended Noble and Greenough School in Dedham,

Massachusetts, graduating in the winter of 1945 and entered Harvard College for a term

prior to entering the Navy just before V-J day. He graduated from Harvard with the class

of 1948.

Worked for United-Carr Fastener Corporation for

17 years in their sales department. Then became a Manufacturers Representative, first with

an existing firm, and later forming his own company, Grant Associates, representing firms

in the custom manufacturing business. In 1997 his son Robert bought the business and is

currently running it successfully.

Cornelia Paine was sent by her father, Robert T.

Paine, of Redlands, to Boston to attend the Katherine Gibbs School, during which time she

met Halcott; they were married in 1953 and had 5 children, 4 boys and a girl..

(Incidentally, Cornelia’s Grandfather,

Charles Treat Paine, and her Great Grandfather, Charles Russell Paine, were both past

Presidents of the Fortnightly Club.)

After selling his business in 1997, they moved

from Weston, Massachusetts, to Cambridge, Massachusetts, before coming to Redlands in

2000. They live on the property where Cornelia’s family have lived for several

generations.

Halcott served as a Trustee and President of the

Meadowbrook School in Weston, a small private primary school , as a member of the Weston

Town Building Committee and as a member of the Town of Weston Finance Committee for 7

years.

He is a member of the Society of Colonial Wars in

Massachusetts and a Fellow of the Massachusetts Historical Society, founded in 1791. He

currently serves on the Board of Directors of the Redlands Symphony Association.

|