|

4:00 P.M.

April 28, 2016

841 Days in Captivity

Dr. Steve Loper’s Experiences as a POW During World War II

by Ronald Helbron D.D.S.

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public

Library

It was about one year after I was discharged from the U.S Army Dental Corps that I had an opportunity to return to Redlands to take over the practice of Dr. Gordon Bennett while he recuperated from an illness. Dr Bennett owned a three suite office building at 340 Cajon St. where the north parking lot of the Beaver Clinic is today. In one of the suites was a new Orthodontist Dr Steve Loper. Steve and I became good friends over the years and latter when he and two others decided to build a new Professional Building at 232 Cajon St, I signed on to be one of the first tenets along withSteve, Pat Vieten D.D.S. and Stan Weisser in the new Pharmacy next door to me.

During the many years that I practiced next to Dr Loper he never mentioned his experiences in WW II. It was only after he retired that he told to me that he had written a short paper, for his grandchildren, on his experiences as a US Army soldier and prisoner in a number of Italian and German concentration camps. The following paper, I hope, will give you something of his personal background and his capture and the horrendous time as a POW. I would like to thank Don McCue, Director A.K. Smiley Public Library for his help in this endeavor. Unfortunately, Loper’s military records, along with millions of others, were destroyed in the fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St Louis MO. I have therefore used his personal records, limited personal interviews, and documented research to construct this Fortnightly Paper. horrendous time as a POW. I would like to thank Don McCue, Director A.K. Smiley Public Library for his help in this endeavor. Unfortunately, Loper’s military records, along with millions of others, were destroyed in the fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St Louis MO. I have therefore used his personal records, limited personal interviews, and documented research to construct this Fortnightly Paper.

Steve T. Loper was born March 11, 1920 in the small town of Chatom, Alabama and grew up with two brothers in the even smaller dirt poor backwoods town of Sims Chapel, Alabama. He, to my knowledge, very seldom wanted to talk about his upbringing, as it brought him a good deal of sadness. His family had a history as turpentine harvesters, which I’m sure was a very marginal income source during the depression. After graduating from High School he enlisted in the U.S. Army, Field Artillery as a Private on January 17, 1941and later he was promoted to a Corporal.

Before I go further with this I would like review a little World War II history that led up to Corporal Loper’s capture in Tunisia.

No one can understand the ultimate victory of the Allied powers in World War II without some grasp of the large drama that took part in North Africa between 1942 and 1943. We learned so much by trial and errors during this period and weeded-out many difficulties in dealing with stubborn British and French military commanders.

Early in 1942, the U.S. under chief of war plans for the Army’s General Staff, Dwight D. Eisenhower had helped draft the first blueprint that would initiate an invasion by Allied forces across the English Channel and invade France with forty-eight American and British divisions. Churchill and his commanders initially agreed to the strategy but then backed away because of the terrible losses they had incurred at Dunkirk, Norway and Greece. The Germans at that time had a 6 to 1 air advantage and could reinforce their troops much faster than the Allies in Europe.

North Africa seemed like a much more plausible place to start a campaign. Churchill had previously suggested that an occupation of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia could trap the Africa Korps between the new Anglo-American force and the British Eight Army fighting Rommel in Egypt. A decision was then made and agreed upon to initiate Operation Torch, the daring amphibious invasion of Morocco and Algeria. After three days of hard fighting against the Vichy French, American and British troops pushed deeper into North Africa. But the confidence gained after several early victories soon wanes; once Allied forces engage the Germans, it becomes apparent that they have more than met their match. The Allies—particularly the Americans—discover that they are woefully unprepared to fight and win this war, in part due to lack of experience, in part due to an unwillingness to pay the necessary price in blood.

Early February,1943 were very dark times for our troops in Tunisia. The German Army and Air Force had inflicted terrible losses on our men. The weather had been cold and raining and the opposition had superior tactics and weapons. This was the first time that we had to deal with the massive Mark VI Tiger tanks: developed as a birthday present for Hitler the previous spring, They were 60-ton monsters with a 88mm main gun and frontal armor four inches thick and capable of destroying an American Sherman tank from a mile away.

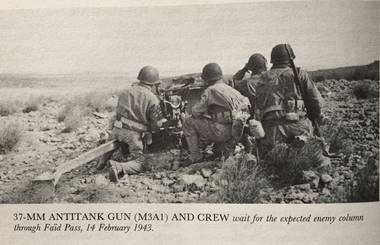

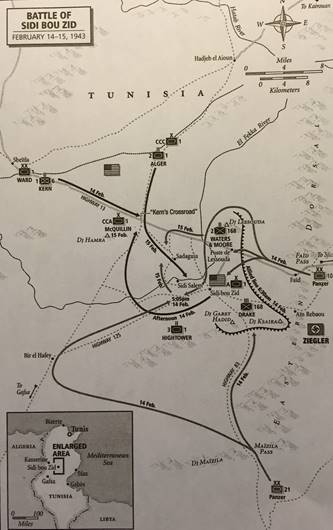

It was on February 14, 1943 that newly arrived Corporal Steven Loper and his Field Artillery Observation Battalion of Company A of the 1st Armored Division were in the wrong place at the wrong time. At about 4:00 A.M. that Sunday morning German soldiers carrying lanterns in black tunics tramped down highway 13 out of Faid Pass to guide more than a hundred tanks - a dozen Tigers among them - along with many trucks and half-tracks. As dawn spread across the plain, the commander of Operation

FRUHLINGWIND, General Heinz Ziegler - a Russian Front veteran looked down on the American positions and liked what he saw: nothing. The Americans did not appear aroused, or even alert. At exactly 6:30 A.M. the drivers shifted into gear and the 10th Panzer Division slammed into our Army positions. Within a few hours of being strafed by Luftwaffe Stukas and Messerschmitt 109’s the Panzer tanks showed up and Corporal Loper and his crew were surrounded near the small village of Sidi bou Zid, and their capture came quickly. They were disarmed and told to start marching. “From that moment on, until the end of the big war, life became a matter of making the most of a bad situation and trying to survive” Corporal Loper said. He was very lucky not have been killed on that infamous day. On a side note, Lt. Col. John Waters, George Patton’s son in law and commander of Loper’s unit, was captured that same afternoon and spent the rest of the war in Germany with Loper. FRUHLINGWIND, General Heinz Ziegler - a Russian Front veteran looked down on the American positions and liked what he saw: nothing. The Americans did not appear aroused, or even alert. At exactly 6:30 A.M. the drivers shifted into gear and the 10th Panzer Division slammed into our Army positions. Within a few hours of being strafed by Luftwaffe Stukas and Messerschmitt 109’s the Panzer tanks showed up and Corporal Loper and his crew were surrounded near the small village of Sidi bou Zid, and their capture came quickly. They were disarmed and told to start marching. “From that moment on, until the end of the big war, life became a matter of making the most of a bad situation and trying to survive” Corporal Loper said. He was very lucky not have been killed on that infamous day. On a side note, Lt. Col. John Waters, George Patton’s son in law and commander of Loper’s unit, was captured that same afternoon and spent the rest of the war in Germany with Loper.

There were about 50 or 60 men in his captured group and they were headed along by a single panzer tank and a half a dozen guards. They marched north-east for several hours, stopping for the night near a German headquarters. The next day they were trucked to a large airport near the city of Tunis. They were given a ration of soup, bread and cheese. “We may have been served camel meat, as there were camel heads and hooves in the garbage pit”, Loper remarked.

The airport was very busy with transports and fighter planes taking off and landing. After a long wait they were hurriedly led to a loading area where they were ordered to board a Junker - JU 52 transport, which was equivalent to our DC-3, but with three motors and a fixed landing gear. There were about 16 POWs, including Loper, all from his outfit. He said, “there were many transports flying together at a low altitude with Me 109 fighter planes flying higher for protection and it took them 40 to 50 minutes to get to Sicily”.

The next two weeks were spent in a camp near Palermo run by the Italian military. He said, “it was a bad place, wet and depressing. The food was very scant and unappetizing. Almost everyone came down with dysentery. All of his group spent the days carrying rock to make a cobblestone roadway”.

Eventually his group was put aboard a passenger train that was headed toward the city of Palermo and onto the straights of Messina, where Sicily is the closest to the boot of Italy. Loper said that when they arrived at the docks at Messina, the air raid siren sounded and bombs started falling all around. One just missed a tank car loaded with fuel near them. A German guard used his foot to push a small incendiary bomb into the water. He said they ran into buildings on the dock for protection and evidently he was slightly injured from flying debris. After that the passenger car they were in was placed on a ferry that crossed the straights to Italy. They were then connected to a new engine and they were on their way north to the town of Capua. The train passed through the City of Pompei where he traded his high school class ring for four loaves of bread and 50 lira. He shared the bread with his buddies but didn’t know what happened to the 50 lira. Soon the train arrived at their POW camp, Campo P. G. 66 near the city of Capua, not far from Naples. This would be their home for the next five months. Everyone was depressed and their future did not seem too bright. Loper soon developed a fever, apparently from a wound he had received during the bombing back in Messina. An area on his back had turned a dark color and was swollen. A German physician removed debris from the wound and the area was dressed and treated with sulfa drugs.

The Italian guards were always singing operatic pieces as they walked guard at night. Loper’s buddies thought they were afraid of the dark. On the 26th of March rumors spread around camp that Tunis had fallen to the Allies, but it wasn’t until May 6th that Tunis was finally taken and the Germans surrendered. Occasionally, the Germans came to the camp to get POWs to work on the docks in Naples. They would all volunteer hoping to get a chance to escape, or be taken in by friendly Italians. On one occasion one of the POWs jumped off the truck that was transporting them and started picking fruit near a farmers house. A man ran out of the house with his shotgun in hand. The German guard immediately pulled his Lugar pistol. Loper was sure that they would witness a shootout, but the Italian backed down.

Dr. Loper told me on one occasion how majestic Mt. Vesuvius was which happened to be in plane view of their Campo 66. He said steam would release from the top almost every day and form clouds that would form in the afternoon. In August of 1943 news came that Mussolini tried to abdicate his position as head of the Italian government. Dr Loper and his buddies all had high hopes of being freed: however, the Germans rounded everyone up and all the POWs were put aboard a train and told that they were going to Germany. Each box car held about 40 men. He remembered that the floors were covered with straw and that there was just enough room for them all just to sit down. Each car had a 20 liter bucket to use as a latrine. After a day or so the latrine would overflow and the whole car would become very messy and smelly. The train would stop two or three times per day for fuel and water for the boilers. On some stops they were given a chance to empty the “honey bucket”. and occasionally, at some of these they were given meager rations of barley soup, bread and water. On about the fifth day they reached to Alps and went through Brenner Pass. The group would take turns peeking through cracks around the door to see the beautiful Swiss scenery. On the eighth day of their journey they reached their destination, Stalag IIB in the northern part of Germany, near Poland.

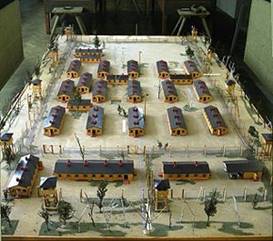

The camp was situated on a former army training ground, and had been used during World War I as a camp for Russian prisoners. In 1933 it was established as one of the first Nazi concentration camps, to house German communists. In late September 1939 the camp was changed to a prisoner-of-war camp to house Polish soldiers from the September Campaign. In December 1940, 1,691 Polish prisoners were recorded there. In June 1940 French and Belgian prisoners from the Battle of France began to arrive. To make room for them many of the Poles were forced to give up their status as POWs and became civilian slave labor. In November 1941 a typhoid fever epidemic broke out. It lasted until March 1942 and an estimated 45,000 prisoners died and were buried in mass graves. The camp administration did not start any preventive measures until some German soldiers became infected. Loper’s group arrived a little more than a year latter.

After they arrived at Stalag IIB, they went through delousing and were given dog tags, which he still remembered his number—-20394. Stalag IIB was “a depressing and desolate place.” Loper said, the barracks were dreary and dark with no ventilation and rows of straw covered bunks stacked four beds high. There were scant facilities for personal hygiene or privacy. “The smell of death was everywhere.” Stalag IIB was most depressing place and time that he had experienced in all of WWII.

Within three days after arrival at Stalag IIB, Hauptmann Springer, their German commandant said all POWs except non-commissioned officers would be required to work for the Fatherland. There were approximately 50 with technical ratings in Loper’s group. Springer said that they were not NCOs would be sent be sent out on work details to farms, factories or both. All the POWs with technical ratings were called outside the barracks and lined up in rows of threes. A spokesman for his group told Springer that they were non-commissioned officers and were not required to work as so stated under the Articles of the Geneva Convention. The German commandant said “You will arbeiten.” Everyone in Loper’s group shouted “nix arbeiten!”, then someone hollered “Attention”. Everyone stood up straight and came to attention. Then someone else started singing God Bless America. They all sang along and then they sang The Star Spangle Banner. Commandant Springer could stand it no longer and ordered the guards to “fix bayonets”. Then he gave them the order to charge the formations of POWs. The guards showed no inclination to hurt the prisoners and acted by “goosing” a few men but not injuring anyone. Then they were swiftly dismissed and went to their barracks.

Treatment of American prisoners at Stalag IIB was said to be worse than any other camp in Germany. Although Loper never experienced anything like this. But harshness at the base Stalag degenerated into brutality and outright murder on many occasions. Records from this camp showed that 10 Americans in work detachments were shot dead by their captors.

Typical of the circumstance surrounding the shootings are the events connected with the deaths of PFC Dean Halbert and Pvt. Franklin Reed. On August 28 1943 these two solders had been assigned to work near the Stalag. While working in the fields, they asked permission to leave their posts, to relieve themselves . They remained away from their work until the work detachment guard become suspicious and went looking for them. Some time later he returned them to the place where they had been working and reported the incident to his superior. Two of the work-party guards were then instructed to escort the Americans to their barracks. Shortly after they had departed, several shots were heard by the rest of the Americans. Afterword the two guards returned and reported that both Halbert and Reed had been shot dead for attempting to escape.

At another Kommando under Hauptmann Springer’s command, the Germans shot two Americans, stripped them and placed the bodies in the latrine, where they lay for two days serving as a warning to other POWs. Eight killings took place in the latter months 1943, one in May 1944 and another in December 1944. In almost every case the reason given by the Germans for the shootings was “attempted escape”. Witnesses, however, contradict the German reports and state that the shootings were not duty; but clear cases of murder.

As bad as this was, German prisoner-of-war camps for western Allies had a rather low death rate of less than five percent compared to a 57.8 percent death rate for German POW camps for Red Army soldiers. It was during this time that both Hitler and Stalin were annihilating millions of Poles, Ukrainians and Jews in the areas surrounding Stalag IIB. It is said, that as many Soviet prisoners of war died on a single day in autumn 1941as did British and American prisoners of war over the course of the entire Second World War.*

While at Stalag II-B representatives of the International Red Cross came to inspect the camp to see if it was in compliance with the mandates of the Geneva Convention. The Germans hastily cleaned and scrubbed the barracks and made sure everyone had good blanket and new straw in their mattress. The Red Cross made a huge impact on Dr. Lopers existence in these camps. But more on that latter.

The experiences that Loper had at Stalag II-B left him with a deep sense of loyalty and love for both his country and comrades. The hope of returning home to the USA was vague and seemed a long way off for him. A few times he went to his barracks, isolated himself and cried. This was one of the most depressing times in his captivity. When the commandant said “no arbeitin “ “no essen”, he thought to himself and said, “ I may have to work for the Germans to survive”.

But to his surprise two days later all of his group were called outside and were told that they were being sent to Stalag Luft III, which was near Sagen Germany about 100 miles southeast of Berlin. Loper said to himself that this transfer has got to be better than where they were now. So the next day they went back into small box cars, heading for Sagen. They went through a suburb of Berlin which had a lot of damage from the bombing. Later that afternoon they arrived at their destination Stalag Luft III.

This was a Luftwaffe-run prisoner-of-war camp, which would be a big plus for Loper’s group as the German Air Force was known to take much better care of POWs than their counterparts (SS and the like).This camp site was selected because it would be difficult to  escape by tunneling. But surprisingly, the camp is best known for two famous prisoner escapes that took place by tunneling, which were depicted in the films The Great Escape (1963) and The Wooden Horse (1950). This camp was mainly composed of British and American officers and NCOs. The North Compound where the Great Escape took place, opened in March 1943.and was composed of British airmen. Contrary to The Great Escape movie, starring Steve McQueen, there were no Americans involved in either escape plan, but Loper noted that some Americans were involved in disposing of the soil from the tunnels. A South Compound for Americans was open in September 1943. Loper’s group probably arrived in February or early March 1944 and they were located the Center compound, because he remembers the escape incident which took place on March 24, 1944. Each compound consisted of fifteen single story huts approximately 10 by 12 feet that slept fifteen men in triple bunks. escape by tunneling. But surprisingly, the camp is best known for two famous prisoner escapes that took place by tunneling, which were depicted in the films The Great Escape (1963) and The Wooden Horse (1950). This camp was mainly composed of British and American officers and NCOs. The North Compound where the Great Escape took place, opened in March 1943.and was composed of British airmen. Contrary to The Great Escape movie, starring Steve McQueen, there were no Americans involved in either escape plan, but Loper noted that some Americans were involved in disposing of the soil from the tunnels. A South Compound for Americans was open in September 1943. Loper’s group probably arrived in February or early March 1944 and they were located the Center compound, because he remembers the escape incident which took place on March 24, 1944. Each compound consisted of fifteen single story huts approximately 10 by 12 feet that slept fifteen men in triple bunks.

Loper remembered that Stalag Luft III was much better, well organized, and cleaner with showers and that the “kartoffels” were a bit larger and the “suppa” thicker. He developed a dental cavity which was restored by a British Dentist. Security was also much greater as many high-ranking officers were interned there. 2,500 or so air force personnel occupied the camp including Major General Vanaman and Brigadier General Spivey. He felt that they were supposed to be orderlies for the officers, but they did not want them to be around as his group might breach the officers security. Dr. Loper did relate to me that they had access to a radio and received daily BBC news which was very good for morale and it gave them hope that the war would be over soon.

On March 24, 1944 the third of three tunnels was completed. It was nicknamed “Harry” and was approximately 30 feet deep and 100 feet long. That night 76 men from the British, Canadian compound escaped. The 77th man was noted by guards and stopped and most of the rest were captured and returned to camp. Hitler ordered the camp commander to shoot all of the escapees and 50 were put to death until the murders were stopped by the head of the department in charge of prisoners of war because it was a violation of the Geneva Convention. Loper remembered that 10 to 12 escapees being returned to camp and subsequently they were put in solitary confinement.

Some time after the escape attempt, as the air war intensified over Germany, their compounds filled to over capacity. In order to make room for the captured airmen the Germans decided to move all enlisted personnel to other camps. Loper and his NCO buddies were again in boxcars, this time being sent to Stalag II A, which was located approximately 100 miles north of Berlin. It was here that Corporal Loper met up with three of the men from his original outfit in North Africa, the First Field Observation Battalion. The camp wasn’t as bad as some, especially Stalag IIB. They could walk around the perimeter for exercise and it was located on the banks of a canal where they could watch various types of watercraft go by. Loper learned to play chess there, which was a good way to while away the time. They were paid one Deutschmark per day, but there was not much available to buy except toothpaste. He eventually got hold of a 2 Deutschmark coin to make a ring..The metal was very soft and malleable so he hammered the perimeter of the coin with a stone, spreading it until it was thin. When it was the right diameter he cut out the center with a small pen knife. The swastika was plainly visible on the inside surface.

The weather in that part of northern Germany was quite pleasant in summer with an average daytime temperature of 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Winters were cold with average daytime temperatures 28 to 30 degrees, and nights about 18 to 20 degrees with quite a bit of snow. By 1945 his old uniforms were getting pretty well worn out. Fortunately his overcoat was in pretty good shape and kept him fairly warm.

February 1, 1945 brought great change to all of the POWs in Stalag IIA. The Russian Armed forces were approaching from east and they could hear the shelling from their artillery. The advancing Russians gave the prisoners a good deal of hope and joy that the war would soon be over. The Germans told them that the following day they need to be ready to evacuate camp by 9 am and to bring any food they might have with them. Loper said they left camp, heading west, crossing over the Oder river. The line of POWs stretched for about a mile. The weather was cold, cloudy with occasional snow flurries and the roads were packed with snow and sometimes slippery. German guards with rifles were stationed approximately every 30 yards and they were allowed a break every hour of so for a short rest. At night they stropped and slept in barns or hay stacks or wherever they could find shelter.

Being incarcerated for two years left many in poor physical condition and after on or two days some POWs were beginning to weaken. A wagon drawn by a team of large horses was used to transport the ones that could not walk any further. No food was given them during the entire march. They ate only the food they brought with them from the Red Cross parcels. Several days into the march they came to some military fortifications were being constructed and they were told by an S.S. officer that if anyone stopped moving they would be shot. For some reason Sgt. Johnson, a paratrooper captured in Holland became a victim of the S.S. by being shot through the head. Someone was kind enough to cover his face with his overcoat and all behind had to step over him as they moved onward.

There were many foreign prisoners with striped clothing working in the area. They were extremely emaciated he said. Others appeared to be walking skeletons. There were 50 or so laying dead. They appeared to have been working until they died. A very young one of the prisoners came close to Loper and tried to say something in a language he did not understand. He was extremely emaciated with deep sunken eyes. A S.S. guard pushed him away with his rifle. These scenes, Loper said, were the most gruesome he experienced in all of World War II.

After eight days of walking westward approximately 65 to 70 miles the POWs arrived at their destination near the town of Luckenwald. Russian prisoners had cleared the area of trees and put up a large tent, like those that were used for circuses. The tents housed about 400 American POWs, but there were no beds, therefore Loper and his group along with others had to sleep on the cold ground. At night everyone slept very close to each other to keep warm and and because the Germans packed as many men into each tent as they could, (it reminded him of pigs sleeping together). Ever so often someone would holler out “everybody turn” so we would all turn over to the opposite side. Loper stated that “It seemed that I always had rock of a tree root under my hip”.

The day to day routine was an exercise in misery, hunger, cold, and lice. A chief preoccupation involved tediously removing individual lice form one’s garments. Showers were a rarity and only two outdoor facets provided fresh water for the prisoners. The German ration was one daily ration of soup, usually barley, potatoes, some being rotten, a slice of bread and once and a while cheese. The bread was very hard and coated with sawdust. It had a date on each loaf stating when it was baked, usually 1939.

Loper remember that it was here that his old G.I. issue shoes finally completely feel apart. On one of them, the sole and the top separated and bounced up and down when he walked. Couple days later he obtained a new pair which he thought were made by Polish internees. The tops and the bottoms were fastened together with pliable strings of wood. All he could remember was that they were very very uncomfortable.

In a personal conversation with me before he died, Dr. Loper related his admiration for the Red Cross during his captivity. He told me he did not think he and his buddies could have survived without the weekly 7 to 8 pound parcels that they received. In Italy the diet was soup and bread and in Germany as I mentioned previously they added potatoes, cheese and occasionally small bits of meat in the soup. The Germans boasted that POWs had a well balanced diet of 1500 calories per day but it was more like 700 to 800 calories. The Red Cross parcel contained a can of powdered milk, a tin of corned beef or spam, sugar cubes, instant coffee, raisins or prunes, cheese, chocolate bar and a pack of cigarettes. Most importantly the Red Cross enforced the Articles of the Geneva Convention.

The Russian POW had it much worse than the Americans. This was probably  because the Germans had been doubled crossed in Poland, lost the battle in the east and primarily because the Russian Government never signed the Articles of the Geneva Convention. Loper witnessed a Russian POW camp nearby. They would hold up the dead when being counted to get another ration of bread. He said, “the dead were hauled out each morning in a wagon”. They were buried in a large trench about seven feet wide and 6 or 7 feet deep. They were stacked in the trench like cord wood. When the trench was almost filled it was covered with soil. You could always tell when the Russian POWs were nearby the air reeked with a putrid odor. Some Russian POWs in the camp were tortured by being exposed to hot and cold. Others were used in medical experiments. because the Germans had been doubled crossed in Poland, lost the battle in the east and primarily because the Russian Government never signed the Articles of the Geneva Convention. Loper witnessed a Russian POW camp nearby. They would hold up the dead when being counted to get another ration of bread. He said, “the dead were hauled out each morning in a wagon”. They were buried in a large trench about seven feet wide and 6 or 7 feet deep. They were stacked in the trench like cord wood. When the trench was almost filled it was covered with soil. You could always tell when the Russian POWs were nearby the air reeked with a putrid odor. Some Russian POWs in the camp were tortured by being exposed to hot and cold. Others were used in medical experiments.

Corporal Loper made the tents in Luckenwald his home from February10, 1945 until the conflict was almost over. The Russian armed forces liberated the area in mid April on their big drive to Berlin. The German guards disappeared one night and the Russians came the next day. Everyone was so happy and excited and their thoughts turned to leaving camp and hopefully going home. The next day some of Loper’s group decided to leave the camp and go to the nearby town of Luckenwald. Many Russian soldiers were there, many of them drunk on vodka. Rape of German women and young girls was commonplace. The Russians were dismantling high tech factories. German soldiers were being rounded up to be shipped to Russia. As soon an they were identified as American by the Germans, the Russians immediately welcomed them. While in Luckenwald they stayed in a large 3 story house which was occupied by two or three German families. Loper said, that each of his group selected a large bed with down covers. (The bed felt so good that he slept a full 24 hours.)

On the first or second of May, 1945, six of them said goodbye to the camp at Luckenwald and started walking southwestwardly. Their destination was the Elbe River about 35 to 40 miles away. That same day they came upon an abandoned German military base. They collected a few souvenirs including two rifles with ammunition. At night they slept wherever they could find shelter, mostly in abandoned houses. On one occasion a Russian officer gave us a voucher to obtain 4 loaves of bread at a German bakery. One day they rode on farm wagon pulled by a tractor which had been confiscated from a farm. The Russian driver was drunk on snaps and they weaved back and forth on the road. All of Loper’s group were afraid, but they covered a lot of distance. They all drank vodka with other Russians and toasted President Truman and Premier Stalin. On the forth day, May 6, 1945 they reached the east bank of the Elbe river.

After some hours of waiting they saw a small motor boat moving down stream. After waiving and shouting in English, the boat turned around and moved to the bank near them. The man operating the boat said, “Bon jour Monsieurs.” He was French, captured in 1939 or 1940. About that time a young German soldier, who appeared to be 16 or 17 years old, approached the group. He was crying and pleaded to take him with them. He said he was afraid of the Russians. Loper’s group debated whether or not to shoot him. The vote was taken, and it was decided he was not a Nazi and deserved to live. They soon convinced the Frenchman to take all of them across the river, saying that the Americans would pay him for his services. The Elbe here near the city of Torgau was about 600 yards wide. They all climbed into the boat and headed for the opposite shore.

As Corporal Loper stepped from the boat unto the west shore of the Elbe he said his heart started to pound heavily. His breathing became very rapid and hard as he tried he could not control his emotions. A great feeling of relief came over him as they started up the river bank and they heard a voice in English; “Halt, who goes there”. They all answered “American prisoners of war returning”. The voice demanded, “advance and be recognized.” They all moved up the bank where an American soldier stood. He shouted, “Sergeant of the guard”. Close by there were two machine guns and several rifleman. The Sergeant arrived and said their Lieutenant would arrange for transportation to take all of Loper’s group to a base near Leipzig.

They all went through a “delousing” station. Some got new uniforms; however Loper did not because they did not have his size, so he said that “I was stuck with the same old clothes with thousands of wrinkles and the same old shoes made by Polish prisoners.” However, he said, “I did not care or complain.” In a day they were on a C47 transport headed for France and the good old U.S.A.

After a period of soul searching and odd jobs Dr. Loper took advantage of the GI Bill and enrolled in Tulane University for undergraduate studies. It was here that he became interested in Dentistry as a career and subsequently transferred to the University of Michigan for his dental degree and postgraduate studies in Orthodontics. Dr Loper became the first full-time Orthodontist in Redlands in 1959 and enjoyed a very fine practice here in Redlands until his retirement in 1999. He passed away August 11, 2008. This exceptional man was 88 years old.

BIBLIOGRAPH

BOOKS

Rick Atkinson,An Army at Dawn, The War in North Africa 1942-1943, Henry Holt and Company, 2002

George F. Howe, U.S. Army in World War II, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, Northwest Africa: Seizing the initiative in the West.

JOURNALS

Steve Loper, Memories of being a Prisoner of War, February14th 1943-May 6th,1945

NEWSPAPER ARTICLES

Former POW also a hero to his community, Redlands Daily Facts, Aug. 26 2008

WEBSITES

Reach into the past, Steve T. Loper Jr. - Prisoner of War Record.

Steve T. Loper Jr. held at Stalag Luft III POW Record

Steve T. Loper Jr. World War IIPOW Germany

Campo P.G. 66

Stalag II B

Stalag Luft III

Stalag II A

Luckenwalde

KEY WORD

Steven T.Loper, POW

BIOGRAPHY

W. Ronald Helbron was born in San Bernardino, California in 1938. He moved to Redlands in 1944 when his father Bill and fellow Fortnightly member Steve Stockton’s father Karp along Karp’s brother Gail opened Stockton-Helbron Sporting Goods. In 1956 he graduated from Redlands High School and San Bernardino Valley College in 1958. In 1963 he graduated from the U.S.C. School of Dentistry and married his wife Nikki. Ron then joined the U.S. army and became a Captain in the Army Dental Corp., stationed in Stuttgart, Germany from 1963 to 1965. Upon returning from Europe and completing his tour of duty with the U.S. Army he briefly practiced in Orange County and then returned to Redlands, where he had practiced for over 50 years.

Ron is now retired and has been involved with a number of community organizations over the years. They include: member and past board member of Redlands Rotary for 50 years, a past board member of the Friends of Prospect Park, Redlands Y.M.C.A ten year board member and President 1994-1996, past board member - Kimberley Shirk Association, Assistance League of Redlands volunteer dentist and past member of it’s Dental Advisory Committee.

Ron has been married to Nikki for 53 years and they have two daughters, Karyn Kasvin, Kristine West and 9 grandchildren.

|