Eugene Delacroix’s Women of Algiers in their Apartment, painted in 1834 is central to the archive of Orientalist images which continue to permeate Western consciousness. In 1955, Pablo Picasso rendered his Women of Algiers in their Apartment, and Algerian feminist author Assia Djebar responded to both Picasso and Delacroix in her 1999 book, The Women of Algiers in their Apartment. The production and reproduction of images such as Women of Algiers demonstrate the persistence of colonialist attitudes and manipulations after the colonial period. The continued currency of these images signals the perpetuation of power structures that maintain the hierarchy of the West over the non-West – an idea that Djebar’s text seeks to uncover. She utilizes the image to supplement her ideas about space and to explore the ways in which images have the ability by means of framing, to divide the world into manageable distinctions that serve as mechanisms of control. Visual representations of the non-Western Other present the Western viewer with affirmations of this order and recall a history of its creation and continuation. Literary critic Edward Said called the process of setting up this kind of relationship between “the West and the rest” Orientalism. He argued that the West created a space to serve as its lesser opposite, allowing a “mythology of the Orient” to circulate in the Western imagination (Said 53). Using these ideas as a springboard, this paper will investigate three images which reflect colonial and post-colonial attitudes: Women of Algiers in Their Apartment by Eugene Delacroix, 1834; Harem Fantasy by Antoin Sevruguin, ca 1900; and Afghan Girl by Steve McCurry, 1985. These representations of the non-Western Other exhibit strong similarities despite the spans of time between them. The link that an artistic representation claims to reality makes it much easier for viewers to overlook their complicity in visual (as preceded by cultural, economic, military, etc) conquest and confinement. However, upon further examination, these images can complicate preexisting relationships, despite the West’s continued prescription to the maintenance of the given hierarchy. Using Said’s conceptualization of this relationship, it can be added that the crafting of an image, especially a photographic one, functions as a weapon that creates a silent Other. An image’s ability to transcend a moment in time lends a sense of permanence and naturalization to the relationship.

The way that viewers read these images enhances the binary of the viewer versus the viewed. The notion of the gaze for the purposes of this paper indicates the looking by a person or society in a position of power at a person or image which is made to be looked at, as object and as spectacle. In the images I have chosen, the relative degree to which the viewer or the viewed asserts power constitutes the agency held by that positioning. The gaze performs the enclosing of space, a phenomenon acknowledged and further limited by an image’s framing. Whether or not the subjects of an image look back, the viewer’s relation to the image is established by a limited viewpoint which reaffirms the differences between self and other. The relationship between the Western and non-Western gazes allows for the subjects of these images to be objectified. The Western viewers of these images, male or female, subscribe to the “male gaze” as a set of practices manifest in the relationship. This is not to foreclose the words male and masculine as synonymous with oppressive; instead it is to acknowledge that sexual politics enter the discussion of these images as a result of their subject matter. It is important that the images I have chosen all contain women and are created by men because this amplifies the notion of the non-Western other as feminine, aligning the viewer with the masculine (male) gaze, which is a patriarchal gaze. It would make a difference, for example, if a man had graced the National Geographic cover, because the non-Western other, especially from an Orientalist viewpoint, is feminized in this discourse; the agency of the Afghan Girl is unsettling because she occupies both feminine and non-Western spaces. The gazes that cross in these images (artist, viewer, subjects) are co-conspiratorially fixing. The sense of the civilized (active, changing) versus the uncivilized (passive, unchanging) parallels John Berger’s theorizing that “men act and women appear” (Berger 47, emphasis in original). This kind of cultural history means that the gaze the viewer adopts has elements of singularity and conservatism. However, this is not to dismiss the multiplicity of gazes and potential disruption of the power relations of looking, including the gazing back of women subjects. The gendered aspects of these images feed into the overarching ideas about the West and the rest. These images make problematic the politics of the West/non-West binary, each potentially contributing its breakdown. The gazing back of the women in Harem Fantasy and Afghan Girl establishes a looking relationship which both fixes and undermines the opposition. Still, it is the creation and circulation of these images which speaks to an ideological history and comfort with the system that places the West with power over the non-West in a patriarchal relationship. Theorists Laura Mulvey and John Berger “point out that it is the social context of patriarchy, rather than a universal essential quality of the image, that gives the gaze a masculine character” (Lutz 189). Other theorists rebut the simplistic notion of the masculine gaze and bring in other power relationships, like race and socioeconomic position, in order to acknowledge the overlapping power structures that make up social contracts (Lutz 189). In looking at the three images for this paper, it proves helpful to evoke the kinds of looking relationships in which the viewer’s self establishment is verified by the ability to identify the viewed as other.

These three images, though of two different media, contain highly stylized representations of non-Western women. Edward Said’s Orientalism proposes that “it is Europe that articulates the Orient” and this creator/subject relationship manifests itself in constructions of arbitrary intellectual space (Said 57). The ways in which the Orient gets (re)presented, in literature, images, etc., often creates, or attempts to create, a certain definition that coincides with the political, economic and /or cultural goals of the author and audience. Orientalism is helpful in looking at imagistic representations because it acknowledges the “restricted number of typical encapsulations” of the Orient that the Western eye allocates to its perceived opposite (Said 58). Gazing upon the Other is embedded in a discourse of violence. The very act of looking is the act of owning and creating the knowledge and language with which to speak for and about the Other.

This practice defers the reality of the subject onto a discourse of othering. In her book, The Body in Pain,Elaine Scarry argues that torture, as a means of achieving political goals, denies the body as feeling and exposes the limitations of language. This silencing is literal in terms of images and threatens the agency of the subject. Her book shows that the violence of torture systematically takes away from the reality of the body in pain in favor of the torturer’s worldview. This kind of systematic relationship relates closely to the creation of images. While aesthetitization does not always perform in this way, likening the creation of images to torture, in terms of levels of agency, is potentially enlightening for the ways we think about representation. The West constructs the so-called Orient in a methodical way: “order is achieved by discriminating…And with these distinctions go values” (Said 53-54). The ordering of space requires an invested belief in the establishment of a certain reality. Orientalism creates this “objective validity” by setting up a self/other binary (Said 54). Reality’s relativity is ignored in favor of determining an identity with the self as the “life-giving power” and the other as submissive and negatively defined (Said 57). The space identified as beyond the self, the unfamiliar, requires a rationale which endows difference with power. In order to justify this structure of power, a space must be created in which the non-Western Other has very little agency. Scarry writes that analogical verification is the way by which consuming the human body as a referent for something else affirms certain cultural constructs. The violence of consumption as a means of gaining information restricts the bodily reality of the human subject. For this paper, I contend that these images do just that.

Women of Algiers in their Apartment

These ideas are germane to Delacroix’s painting, Women of Algiers in their Apartment, which represents the European’s possessive gaze. In this painting we see three seated women of light coloring and one standing woman of dark coloring, who moves toward the right side of the frame. We make the assumption that the women’s space is that of a harem because the image reflects what we recognize about a group of women in an enclosed space, and that the standing woman is a servant. The painting attempts to know, through investigative qualities, about the feminine Other of the harem. Within the painting, the three women exemplify the contradiction that the Western gaze wishes to dissolve: they are both timid and displayed. The painting creates a space in which the male gaze finds itself satisfied but not wholly uncontested: the women’s reserve is sexually alluring, something against which the European will have to struggle in order to fully enter their sphere.

A prominent Orientalist artist, Delacroix was reportedly struck by the sights during his visit to North Africa - enough to fervently sketch his memories which he would use for the painting (Djebar 134). In the post-face to her collection of short stories with the namesake of Delacroix’s painting, Assia Djebar offers a useful description of the physical positioning of the women in the painting:

…three women, two of whom are seated in front of a hookah. The third one, in the foreground, leans her elbow on some cushions. A female servant, seen three quarters from the back, raises her arm as if to move the heavy tapestry aside that masks this closed universe… (Djebar 135)

Their positions are seemingly casual, fleeting, caught. Their clothing is ornate and sumptuous. The room is lit from the viewer’s left giving the painting a left to right, downward sweep. The downward movement is further enhanced by the angles of the drapery, the slanted mirror, the cushions on the floor, and the downcast gazes of the women. A servant, furthest right, appears attentive, but moving out of the frame. The brightest part of the painting is the third woman from the left: she is wearing white and her pale complexion is illuminated much more than her company. The eye follows the light to her, and then moves counter-clockwise around the rest of the image. That she is positioned to the right of the painting, that the figures on the right are higher than those on the left and that the painting’s two profiles face left contribute to a counter-clockwise track of the eye. Delacroix’s own art theory shows that he was sensitive to the symbolism of left-right orientation (Porter 33). In this painting, then, he has selected for a Western audience: Westerners read and write text left to write, and perhaps this conditioning applies to visual artwork as well. Generally, what is on the left is greater or of more importance than what follows on the right. There is more space behind the women than in front. The left and right borders are close (but not suffocating) giving both a sense of proximity and that there may be more to this room than the painting is allowing the viewer to see.

None of the gazes of the women cross, and none meet the eyes of the viewer. Through the lens of Orientalism, which situates and engenders the East as female, the Western patriarchal gaze is unchallenged, and voyeurism is carried out without any confrontation. This can be read in a couple of ways, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive: 1) that the agency of the viewer trumps that of the women; 2) that the women are part of an exclusive space in which the viewer cannot participate. The first reading constructs the women as objects to be controlled within this space which the viewer has penetrated through the dominance of the Western male gaze. This reading also reduces the subjects of the painting as fantastic, exotic and as cultural curiosities. The second regards the women’s space as their possession: the viewer does not share in that space. To the Western viewer, this poses a threat. Delacroix seems to deal with this by disallowing the women to share any looks, even while he suggests that the two right seated women may be in conversation or have recently glanced at each other. By maintaining distance between the subjects and the viewer, Delacroix creates tension that both affirms and denies the voyeuristic tendencies, among others, of the Western male gaze.

Although many images of fully veiled women exist, it is possible that this image serves as a space to deconstruct the visual secrecy of the veil, to penetrate identifying markers. Penetration recalls the violence (military, sexual, cultural, etc.) which results in the ownership of space and the assertion of power. In images, the artist and/or the viewer encounter a double-edged sword when a woman without a veil resists this incursion by disabling the artist’s attempt to dissolve her agency. Still, looking at Delacroix’s painting makes the viewer an accomplice of colonial penetration while masking the violence by presenting a beautiful, well-crafted work of art; we are encouraged to look. The painting confronts how power gets constructed through a subjective framework. Aesthetitization may not only or always serve as a mask, but here it does because this space, this room, is the only space in which the women have any agency, but this agency is checked, thwarted, by the painter’s choices: the colonizer frames the colonized.

Through this framing, the artist creates a palatable spectacle. Theorist Laura Mulvey explains the idea of the spectacle in visual art as the source of pleasure. Mulvey’s work on the relationship between the viewer and the cinematic viewing experience explores how film creates woman-as-spectacle while the male gaze deals with the fantasy of control. The space of the cinema “satisfies a primordial wish for pleasurable looking” for which the human form is offered up for scrutiny and narcissistic recognition by the viewer (Mulvey 17). The creation of spectacle allows the human body to be styled, displayed and consumed. Any apprehension that comes from the viewer/viewed relationship is dealt with by controlling the space of the image; the object of the image performs according to the gaze, which dissolves some of that tension.

What the Westerner sees and knows about the non-Western other reflects the containment of the unfamiliar. However, something so limited by unfamiliarity and ‘otherness,’ still retains an aura of familiarity because of its epistemological proximity to the self: “The Orient at large, therefore, vacillates between the West’s contempt for what is familiar and its shivers of delight in – or fear of – novelty” (Said 59). Knowing and, in the case of images, viewing the non-Western Other in pieces reaches toward controlling the world through discriminating practices which serve to erase any supposed wholesome opposition to Western power. Viewing the non-Western Other in this way gives credence to the divisive practices of the powerful over the disenfranchised, by reinscribing that relationship.

Elaine Scarry’s theory of power in The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World addresses the ways in which pain signifies the breakdown of the world for a tortured prisoner (Scarry uses examples of political prisoners tortured for intelligence information). The torturer increases his agency by producing pain and limiting the world of the prisoner to only the felt characteristics of pain by eliminating any other civilizing agents (language, material objects, etc). That pain is unfelt by anyone except the prisoner creates a platform for doubt and for the enclosure of the prisoner’s world, as the torturer’s scope increases. Torture, pain producing, reduces the prisoner’s world while increasing the scope of the torturer through “self-conscious display of agency” (Scarry 27). It is in my interest to apply this “disintegration of the world” to images (Scarry 38). The torturer destroys agency in order to draw confessions, which would justify the torture. It appears that images, while not necessarily agents of pain, perform a similar function of objectifying, minimizing, and enclosing the world of the subject, while attempting to enlarge the viewer’s world. Images, while certainly representative of and containing elements of civilization, utilize framing and borders to limit agency in ways that parallel the deconstruction of the prisoner’s world.

Scarry argues that pain’s verbal inexpressibility creates doubt about pain’s sentient existence. In attempts to express pain, the instability of language is exposed, furthering notions of doubt. To relieve doubt, pain’s attributes need to be abstracted. Scarry explains that through “analogical verification” pain is attributed to “a referent other than the human body” and becomes “certain” as a characteristic of that referent (Scarry 14). It is easier to comprehend an abstracted expression than to empathetically feel pain. Despite the fact that having bodies is our shared experience, the body is placed outside of experience and used instead to verify a belief. The body and the pain get lost in the referents: “we often call on them to convey the experience of the pain itself” (Scarry 15).

When the body and the pain are essentially negated, it encourages structures of power to be built based on the denial of the body and the conflation of the referent. What appear then are the “aura of realness” and a sense of affirmation about a belief that has encountered a crisis – the doubt of another’s pain (Scarry 14). Politically, however, this “crisis of belief” manifests itself in relations of power (Scarry 14). Upon discovering doubt, belief is suspended and then attempts to grasp a referent. The referent takes the place of, and consequently power over, the expression (of pain). When belief resides in a cultural construct, the “truth” is eclipsed. For the purposes of this paper, the construction of an image eclipses the subject of the image in such a way that relocates belief in the material construct rather than the subject and its actual experience. The image maker asserts his power by encouraging belief in the image and disabling the reality (despite his dependence on the reality) in favor of the cultural constructs that coincide with and uphold the belief. Delacroix’s Orientalist painting takes an assumption about the space of the Algerian women and creates a likeness that verifies it. The women’s humanity is less important than the idea that this painting reaffirms what the French already knew about Algerian women.

What the viewer sees is (at least) third degree knowledge that cannot be confirmed because the referent is diluted and obscured by the painter’s subjectivity. The bodily attributes of these women are only certain within the confines of the frame, not in and of themselves. Knowing, the desire to know and to make known, is an invasive practice which, in its attempts to get at the “facts,” becomes spectacle. Their agency has been removed, in part, by their aesthetitization, which only alludes to reality. Given a painting’s function as a referent, we can apply Scarry’s work on pain:

The failure to express pain…will always work to allow its appropriation and

conflation with debased forms of power; conversely, the successful expression

of pain will always work to expose and make impossible that appropriation and conflation. (Scarry 14)

Replacing the word “pain” with “agency” creates a striking parallel. While the scale by which this happens definitely varies, as shown in the images I have chosen, agency is the first line of defense for subjects of looking. Taking this further reveals that in the cases of the torturer and the image maker (again, recognizing scale), the differences lie in the subject (a tortured being or the subject of an image). In Scarry, the “failure” or “successful” expression of pain seems to be a responsibility of the subject of pain. For an image, I would argue that the image maker can be held more responsible for the allowance or denial of agency because the subject is consciously and permanently silenced (a silence which can, nevertheless, be combated through the gaze).

In another aspect of her argument, Scarry discusses how civilization is made up of objects which serve as projections of the human body. These are projections of sentience: what a human is capable of, its attributes, become external and artificial. The torturer unmakes the world for the prisoner by creating a “miniaturization of the world” (Scarry 38). By placing a prisoner in a room with few to no civilizing agents, the torturer removes the prisoner’s bodily proximity and association with objects of the external world. Images are also miniaturizations of the world. The objects within image-civilization contribute to image-agency. An image-maker has the advantage of selecting what will be included in this reduction. In Delacroix’s painting, objects are relatively plentiful: hookah, pillows, clothing, mirrors, rugs, walls, doors, curtains, shoes. These indicators of civilization show that agency is being less countered by a reduction in space than by the subjects’ inability to return the gaze. The control that Delacroix, and by extension the Western male gaze, has over this image is dominating because of the women’s submissive positioning within the frame, rather than the encroachment of the frame itself. The viewer’s relationship to the image becomes one of spectacle and consumerism.

Spectacle derives from (sexual) difference. Within patriarchal society, woman is the sexual other who represents both discomfort and visual pleasure. Mulvey explains that women embody the idea of the castration threat and lack in this society. However, memory creates a very strong device for recognition of “maternal plentitude” (Mulvey 14). The spectacle of a woman appears to compromise the patriarchal order because of the viewer’s identification with the pre-symbolic self. The cementing of desire for this former self creates the space in which woman is the object of fantasy, so often manifested in images. Mulvey also explains Freud’s theory that pleasure lies in “taking other people as objects” (Mulvey 16). Woman is displayed as the natural choice for this objectification and subsequent sexual, aesthetic and economic consumption. The investigation of woman (the Other) allows the male viewer to escape the anxiety surrounding the feminine.

The politics of the gaze highlights the viewer/viewed relationship. The colonial gaze is a gendered gaze based on the self/other, active/passive, male/female binaries. For example, in his discussion of the unveiling of Algerian women, Franz Fanon cites the Western male gaze as a means by which the woman becomes the subject of fantasy as the Westerner projects his desires onto the woman whose visual secrecy frustrates him (Fanon 44). Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism explores the notion of the veil and the Algerian woman, exemplifying the kind of investigation and desire to know and fetishize the other. The colonizer’s frustrated desire stems from the visual secrecy of the woman behind the veil. French colonizers made explicit efforts to unveil Algerian women because they believed by conquering women, they could also control Algerian men, furthering their colonial enterprise. Fanon explains the European’s visual frustration as a sexual frustration, a hindrance to penetration, with the strategy “to cultivate man’s doubt and desire” (Fanon 45). The words “doubt” and “desire” point again to the need of a referent; the male gaze cannot see ‘woman’ and instead relies on a constructed truth about the object underneath the veil. Once the referent, some manifestation of woman, is confirmed, the male gaze is temporarily satisfied. A mere glimpse of a woman “may suffice to keep alive and strengthen the European’s persistence” (Fanon 43). Desire confuses the European, and is relieved only by breaking down the perceived division, by unveiling. The desire to know what is underneath the veil manifests itself in a desire to possess, much like Freud’s pleasurable relief in taking another as an object.

One of the Orientalist genres to which Sevruguin’s works subscribe is that of the “harem woman.” Harem Fantasy is an example of this portrayal of exoticism and intrigue. In comparison to Delacroix’s painting, this portrait achieves a similar goal: to invite the Western male gaze. The woman is seated, assisted by a servant, who bends to hold the hookah. The woman is seated almost identically to the right-most seated woman in the painting: legs crossed, but open, one hand on her knee, the other on the hookah. She is dressed in white, her veil and long braids contribute to her exoticism, and her short skirt makes her available. The lighting in the photograph comes from the right, illuminating her, making her obviously prominent as the servant fades into the backdrop. Both figures gaze into the camera. The simplicity of her dress and the surrounding studio renders her not particularly novel, and her look, though direct, is more accepting than challenging; the male gaze has much more to look at than just her face. The strength of the up and down movement of the eye trumps the horizontal movement because the composition is split by the tall hookah and the dark and light contrast. Again, like Delacroix’s painting, the brightest area is to the right of the image.

Antoin Sevruguin- Harem Fantasy

The viewer is much closer to the subjects of this photograph. While this proximity draws the viewer in, the gaze of the woman is initially deterring. She, unlike the women in Delacroix’s painting, carries some agency through her gaze. She is not only being looked at but makes the viewer aware of her own presence in front of the camera; this consciousness gives her agency. Her ability to look back, however, is trumped by her depiction as a sexual object, something to be consumed. The male gaze is meant to find her alluring, even if only because she is exotic. Her veil indicates her foreignness, which Orientalism explores as a reason for overwhelming curiosity and reductive understanding of the Other. The ability and intent to reproduce this photograph furthers the implication that we should find her available, that we should find the Eastern woman available. Sevruguin’s work in the Orientalist genre, while not always about the harem woman, allows for the penetration of the Western gaze. The photograph’s purpose is to assure us that the “truth” of the image, its representation of (an imagined) reality justifies visual exploitation.

As both a practice and a concept, spectacle verifies for the viewer the oppositions that need to be upheld in order for colonial conquest and commodification to work. By setting up a scene, the discursive elements of colonialist thought are reaffirmed through the sense of artistic access. Framed by the subjective viewpoint of the Westerner, the non-Western Other is typified and representative of all Others. Such representations maintain authority because access means knowledge and ownership, both very powerful mechanisms in the perceptive and material practices of the Western viewer. The forced subjugation of the non-Western other causes and is reinscribed by purported artistic (material) endeavors.

The media of these three images (one painting and two photographs) complicates the comparisons because a painting performs differently than a photograph in terms of viewer relationship to the image and the subject(s) of the image. In both media, the authors have made choices. The differences between the two mediums lead to some different conclusions about authorial control. Paintings tend to be perceived as products of imagination, while photographs carry an assumption of objectivity (Savedoff 96). A painting retains an aura of fiction, but is emblematic of stories, perceptions, events because it takes a recognizable form which reminds the viewer of tangible elements in reality. A painting’s singularity also enhances the uniqueness of the subject. Paintings, while certainly capable of “accurate” representations, are perceived differently than photographs, which, as products of machinery, are supposed to be reflections of a scene and which must depict reality as a conventional constraint. The mechanical nature of the camera and the photograph are part of the industrialized West which has seeped into the non-Western world. The importance of photographic realism in asserting the modern ways of the West over and within the non-West, I think, speaks to an ownership of the Other because it is a Western invention. The ability to capture and reproduce images is about the possession of a subject. When a non-Western Other is placed (sitting, standing, formal, candid) within the viewfinder, the image produced from such an encounter takes on meaning as an object to be replicated again and again.

Photography’s strength, arguably, lies in its assumed objectivity. However, the introduction of both the photographer and the viewer complicates the notion of simple, evidentiary proof. In photographs like those of Sevruguin and McCurry “representation requires a belief in extratextual information” (Blocker 125). The viewer does not come to the image without external influences. These photographs in turn uphold external realities. Photographs’, and to some extent paintings’, function as referents signals already-held beliefs by creating a space that assumes peripheral knowledge. Further, because a photograph functions so strongly as absence, it reveals conflicting feelings of doubt. What we see in the two-dimensional image is, from the moment of creation, missing; that moment can never happen again. The negotiation of these disorienting factors is manifested in the absolute reality of the tangible representation and its “very real effects” (Blocker 123).

The emergence of the camera during the Victorian era heralded a new way of looking. The growth and expansion of empire as a result of industry and invention created a new perspective on ownership. The camera exemplified this growth of science and its products enabled the artist and viewer to perceive “objectivity and accuracy while at the same time stereotyping Orientals through photographers’ careful staging and selection of images” (Behdad 83). This false conception of objectivity enabled the West to justify its actions regarding the colonized Other.

Photography “implied the capture of the largest possible number of subjects. Painting never had so imperial a scope” (Sontag 7). The use of the words “capture” and “imperial” coincides with the new technology’s ability to further delineate the world into subjective boxes. Susan Sontag writes about the emergence of cameras in terms of their potential (and innate) aggressiveness. The act of possession through photography is inherently violent because of the subject’s slavery to dominant idealizations. Photography as technology means that images can be taken, duplicated and consumed quickly and irreverently. A photograph’s ability to be reproduced influences the access a viewer has to an image.When applied to the non-Western other, this allows the viewer to possess a world in which they do not belong and to consequently expect similar representations of the other which reinforce visual and political ideals.

The photographic field quickly moved beyond the borders of Victorian Europe. Often, people commissioned by anthropological or explorational societies set out to capture and record images of the East. Travel accounts in photography and literature fueled more of the same, sparking economic and political interest. Houghton writes that “to look into the Victorian mind is to see some primary sources of the modern mind” (Houghton xiv). The first photographic explorers can be seen as the first tourists, enabling the industry of their homelands to exploit the newly discovered, or rediscovered, east.

In early twentieth-century Iran, photography became part of upper class society because early on it was seen as a science. Those who wished to study it had to be able to afford to go abroad. After photography moved past the experimental phase it was pursued more thoroughly by travel and commercial photographers as a means of recording and advertising (Vuurman 21). Antoin Sevruguin established himself in Iran as the first to make a living solely on photography. While Western photographers came to Iran to record cultural and physical phenomena, and others in Iran simply experimented with the new technology, Sevruguin realized a livelihood from producing images (Stein 112). He was commissioned by European Orientalists to provide the West with ethnographical and archeological information about Iran (Behdad 89). His works show the life and culture in nineteenth-century Iran (Vuurman 22). His photographs encompass a wide range of subjects: he became a court photographer, surveyor and portrait artist (Vuurman 24).

Sevruguin’s photographical efforts were widely used among Western scholars of ancient Iran, but he was rarely given the proper credit for them. His work in creating an Iranian identity was then used for the presentation of Iran to the West (Bohrer 33). Bohrer comments, “the photographic camera is seen as an extension of the sociocultural status of the user” (Bohrer 38). Both indigenous and Western audiences viewed Sevruguin’s work. Sevruguin’s photographs occupy the space between Western authority and Iranian expression because he worked for both Iranian and Western patrons (Bohrer 39). Through his photographs he was able to show “not only the appearance but also the very cultural habits, the ways of seeing, of the time” (Bohrer 35). Sevruguin’s work reflected his multicultural audiences and Orientalist art was a way of encapsulating the East/West relationship. His photographs were widespread in the West and still maintained the aura of objectivity rather than commercialized construction because of Western interest in objectifying the Eastern Other (Sheikh 57).

Sevruguin, as a commercial photographer working for a Western audience, walked the line between Orientalist and Orienteur (one who would take a relatively objective approach in representing, for example, Iran). Perhaps his indication of Eastern agency is only palatable for the Western viewer because he isolates her. Her exotic material signifiers (the hookah, the veil, the cushion, the rug) are much more limited, in terms of quantity and visual stimulation, than the objects accompanying the women in Delacroix’s painting. The framing of this image creates her only in relation to these objects: she, too, is a prop. The staged nature of this image is reductive. It serves as the walled-in world of the subjects that encroaches on and encapsulates the Eastern Other. What is left is the abstracted commodity of the photograph, lifted off of the Other’s space and presented to the Westerner as an artificial representation of constructed Orientalist truths.

It is our investment in the truth that we believe is reflected in photographic representation which can reiterate these beliefs. Susan Sontag writes “it (the photograph) is also a trace, something directly stenciled off the real” (Sontag 154). Photography’s mechanical nature makes it “an incomparable tool for deciphering behavior, predicting it, and interfering with it” (Sontag 157). Trusting photography, whether or not the subject is posed, creates a unique viewer experience in which it is believed that the photographed subject is pre-controlled and ready for consumption. In the instance of Harem Fantasy, the photograph already accepts the Western gaze as a mechanism of control over the Eastern woman. In the photograph, we see a woman offered up sexually, an idea affirmed by the title. By subscribing to Orientalist representations, it reinscribes those ideals and makes it easier for the Western eye to expect that kind of relationship to the image. Further, the woman in the photograph invites us into a space in which our behavior is also predictable. Ultimately, the photograph serves as a plane that separates two truths (about the Orientalist Other and the Western consumer), and as a space where framing attempts to contain the Eastern Other.

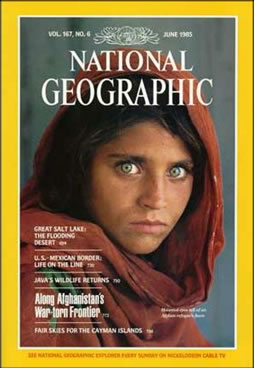

This is quite apparent in Steve McCurry’s famous photograph Afghan Girl, first shown on the cover of National Geographic magazine. The work of Said and Scarry are arguably just as relevant to late twentieth-century works like Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl. The lens of Orientalism is useful in examining more current images because they reflect a historical pattern of thought about the other which has not left Western culture (despite the cultural differences between 1834 and 1985 or 2010, the colonial mindset has simply morphed into what we now call globalization). Further, in attributing the concepts of violence and torture (which in recent years have become a widespread source of political and popular contention) to these images, we are able to examine the ways in which contemporary global society perceives the world in binaries. The containment of the Other and the maintenance of these binaries is still violent and the creation of images that support this way of thinking through certain ideological subscriptions must be considered problematic because they still create abstractions out of real situations in favor of a deferred aesthetitization of that reality.

Steve McCurry’s photograph is an iconic National Geographic cover and most people can recall the look of this famous image. McCurry is renowned for his striking color portraiture and his extensive work in Afghanistan. The image of the Afghan girl comes out of Soviet-occupied Afghanistan of the early- to mid-1980s. We live in a world where the Western photographer can gain access, voluntarily, to a foreign war-torn country and, to be blunt, benefit from the experiences of a victim of violence. The Western photographer has great agency when it comes to representing the other. McCurry has the presumed responsibility of finding a memorable shot, a completely subjective task; his career depends on it. The image itself, sans National Geographic title and captions, sells, for example, as an enlarged poster (USD$65.00) or in greeting card form (USD$12.95 for 24 cards). The commodification of this photograph does a couple of things: 1) it places literal economic value on the photographed subject; 2) it encourages this kind of representation. Added to the cover of a national magazine, the image takes on further meaning as a popular culture text. The girl with the sea-green eyes finds a place on the cover of a magazine which is bought, consumed, collected and stored (as well as contemplated and admired) by millions of middle and upper class Americans. That “collecting and displaying are crucial processes in forming Western identity” has been important for the magazine’s success speaks to the indexical ordering of knowledge which must take place in the collective Western mind (Lutz and Collins 23).

National Geographic’s cultural legitimacy stems from its position as both popular and scientific. As an institution it claims to represent the curiosity of Americans and to be accurate and instructive. Its influence “as an important and reliable interpreter of third-world realities” both reflects and enforces America’s obsession with comparison and cultural difference (Lutz 17). Lutz and Collins argue that National Geographic “took images of Africa, Asia, and Latin America from their historical contexts and arranged them in ways that addressed contemporary Western preoccupations” (Lutz 23). As colonized territories began contesting Western presence, National Geographic was forced to address world changes while still upholding its commitment to accuracy and public interest in an idealized world with America at the top. This is reflected in photography, layout and caption construction and placement. Articles maintain their appeal through definite commitment to informational and easy-to-digest layout and content. Captions are especially important for “direct[ing] the reader toward some meanings and away from others” (Lutz 77).

In National Geographic, “people of the third and fourth worlds are portrayed as exotic; they are idealized; they are naturalized and taken out of all but a single historical narrative; and they are sexualized” (Lutz 89, emphasis in original). The attractiveness of the Afghan girl is guaranteed to the Western reader. She is unusual, exotic and strikingly familiar: her head-cloth, dark hair and bright eyes encompass both spectacle and human emotion. Her face is framed by the drape of the torn maroon cloth, which passes over her shoulder. The light comes in softly from the right, illuminating that side of her face and highlighting the bridge of her nose. The background is a blurred, blank slate blue. She looks directly and piercingly into the camera lens and, by extension, back at the viewer.

Steve McCurry - Afghan Girl

On the magazine cover, the caption: “Haunted eyes tell of an Afghan refugee’s fears” directs the viewer (almost unnecessarily) to her look, to meet her gaze. Without the caption, maybe it is not fear that the viewer perceives, but National Geographic decides that her expression is best pinned as haunted and fearful. Over her shoulder, the contents of the magazine are stamped. The story that refers to her is in bolder, larger print: “Along Afghanistan’s War-torn Frontier”. The word “war-torn” is directly placed over a tear in her head-cloth, which shows a green much like the green in her eyes. What McCurry captures in his portrait is aesthetically pleasing and shows-off technical perfection. The viewer is brought face to face with an exotic other who, despite her “fears,” is not about to look away from the scrutinizing Western eye.

It is important to think about the image simultaneously in terms of an image and as a magazine cover because even as the image stands alone in McCurry’s portfolio, National Geographic is its reference point. The cover of the magazine is an important cultural space: it is seen first, it is prestigious, and the image gets associated very strongly with the magazine’s title. The cover is often what sells the magazine, both accommodating the viewer with spectacle and reinforcing the idea that “this” matters. This image has become incredibly famous because of its association with National Geographic, for its beauty and because it exposes a life and lives which many in the West do not have to experience.

In Myth Today,Roland Barthes states, “myth is a system of communication” (Barthes 293). Myth is the ideological message that comes to us through language, the semiological system. In speaking solely about the image, what we see in the photograph (her torn head-cloth, her bright green eyes, her facial expression, her hair) are the signifiers which form the primary sign “Afghan girl with the sea-green eyes.” To follow Barthes’ line of thinking, this combination becomes the secondary signifier, the “Afghan refugee.” When introduced to myth (ideology), this secondary signifier comes to mean that it is the “Other” who lives in instability, in fear, and in discomfort (and, by contrast, that the self is safe and unharmed). Under the order of myth, “Afghan girl” combined with the signified “Afghan-ness” (fear, poverty) leads to the secondary sign, the signification, “the Middle Eastern experience.” The signification makes the viewer understand something about the image and about the viewer’s place in relation to the image. This connotation of the image is brought about by both what is in the image and what cultural ideologies the viewer adds. The “Afghan girl” becomes the Afghan refugee experience, thus supporting the myth, the ideology, that this is a natural state of the Afghani. Barthes talks about myth in terms of naturalization: “myth has the task of giving an historical intention a natural justification” through semiology (Barthes 300). Even if meaning is a site of contestation through signs and signifiers, myth seems to combat the notion of change in order to provide an assumption about the world as is.

In The Photographic Message Barthes claims that a photograph’s meaning (connotation) can be “inferred from certain phenomena which occur at the levels of the production and reception of the message” (Barthes 19). The photograph itself, Barthes claims, is completely denotative, but the connotative message comes from the consumer’s reading of the signs within the image. The image of the Afghan girl, however much an analogical copy of reality, is connoted by the viewer’s understanding of these signs. This image, at the level of production comes under the banner of National Geographic. In itself, the magazine title connotes a specific representation of reality, as discussed above. The photographic connotations reflect the producer’s and viewer’s ascription to accepted meanings of certain signifieds.

Barthes also addresses pose and objects as signifieds of connotation. The pose of the Afghan girl is three-quarter with a direct stare and set expression. While these factors may be read as nuances of obstinacy or bravery, these are quickly quashed by the fact that it is the photographer who closed the shutter, and her choice in the matter is limited. The objects, namely the head-cloth and the wall behind connote a small space, poverty. It may also be appropriate to consider as objects within this photograph the title and the caption. The accompanying article’s title “Along Afghanistan’s War-torn Frontier” (in bold over a tear in the head-cloth) becomes part of the image. The image’s caption (‘Haunted eyes tell of an Afghan refugee’s fears’) directs the viewer toward a certain reading of the image: the reading that recognizes the look as fearful in order to downplay the accusative intensity of her expression. Barthes claims that the caption can either amplify a set of connotations already given in an image or invent a “new signified which is retroactively projected into the image” (Barthes 26-27). The two kinds of text which share the image space, I think, presume to reflect Barthes’ former claim. However, it is possible that the image itself does not necessarily succumb to the caption’s reading.

The gazing back of the girl in the image is possibly the primary reason it has become so iconic, and potentially problematic. Her eye color, bright sea-green, confounds the viewer and complicates the viewer’s notion of what the Middle Eastern Other looks like. How we expect the Other to look or act makes meaning. Laclau and Mouffe write about articulation as a practice which fixes meaning, because meaning is not essential, is negotiated, and is conducive to the dominant group’s continuation of power. This image is articulated both through its dominant reading (that she is haunted by fear,) and by resistant meanings (that she gazes at the viewer with defiance). Further, her gazing back interpolates the viewer as a subject, which, like Althusser’s example of hailing someone on the street, forces the viewer to recognize his or herself as an ideological subject. The viewer exists because of the look, and the viewer is conscious of their position within the ideology that says, among other things, that the Afghan refugee should not be given the agency to subjectify the viewer. There is tension in the viewer/viewed relationship, but ultimately it is resolved by the function of the medium: she becomes an object of possession. That she looks back from the cover of a magazine, of National Geographic, (an example of Althusser’s material existence of ideology) provides contextual relief. What the viewer feels about National Geographic reaffirms the ideological framework that should exist, despite the Afghan girl’s agency. So really, the viewer is being interpolated twice (once by the gaze and once by the magazine) and there is a conflict, a negotiation, taking place for which of these interpellations will fit within the larger framework of hegemonic experience.

As a portrait, there is an implication that this image is posed. However, once McCurry gained permission to take her photograph, he closed the shutter at a moment when her expression was particularly captivating. The girl’s relationship to McCurry and McCurry’s experience/skill/luck meet to create a beautiful but tense image. As a result, the viewer is presented with a photograph that is both alluring and confusing:

The portrait allows for scrutiny of the person, the search for a depiction of character. It gives the ideology of individualism full play, inviting the belief that the individual is first and foremost a personality whose characteristics can be read from facial expression and gesture. …the National Geographic portrait, like all close-ups of only a part of the body, leaves us with a fragment of a person. (Lutz 97)

The “fragment of a person” allows the viewer to both identify with and to find strange the person in the image. Her familiarity as an embodied being is quickly negated by her lack of body. The viewer, however, is so drawn to her eyes that the rest of her is relatively unimportant for the image. Her gaze seems to pass through the plane of the photograph and respond to the viewer’s scrutiny in such a way that makes the viewer subsequently uncomfortable. That she is female, indicated by the head-cloth and knowledge that the feminine non-Western Other is marked by a veil, makes her gaze all the more remarkable because of the ideas about women as weaker and hidden. Again, it matters that this photograph is of a woman (as opposed to an Afghani man) because it speaks to the alignment of “the Orient” with the feminine. She transcends her sociocultural gender status and stands alone, presented to Western consumerism, powerfully challenging how we read non-Western women, disallowing us to chalk up her position to simple pragmatism or misfortune. And yet, we always have the ability to stop looking, to turn away or put down the image if it gets too uncomfortable, and to dismiss it as popular, unfortunate, or beautiful. While the popularity of this image may come precisely from this discomfort, the image still gets articulated in ways which naturalize her position as Other.

The gazing back also seems to fit within Michel Foucault’s dictum “where there is power, there is resistance” (Foucault 349). And this resistance is always internal to power relationships. The image contributes to the knowledge of this discourse of power, which is amplified by the strength of the resistance that the viewer experiences. The potential for this image to convey knowledge, the function of discourse, is based in the power relationship it creates. “Discourse transmits and produces power; it reinforces it, but also undermines and exposes it, renders it fragile and makes it possible to thwart it.” (Foucault 352) We find the confrontation embedded in the discourses of race and gender that are central to this image. That she is from the Far East speaks to a long East/West relationship that generally places the West in a dominant position. Her gender matters because it potentially breaks or reaffirms notions about women and agency between the sexes. In this image, the gazing back exposes the discourses of power, which in our everyday “naturalization” of things, we are not forced to confront. It is possible, then, to view the image with reservations about the relative power of the viewer and the viewer’s ideology. If the viewer assumes a male gaze, they encounter a woman who is looking back in such a way that resists penetration. Foucault allows for “a multiplicity of discursive elements” which is distributed according to positions of power (Foucault 352). However, even as power depends upon resistance in discourse, there is still a reaffirmation of dominant ideologies because the resistance gets incorporated into the power relationship. The girl’s gaze directly meets the eyes of the viewer; the look upsets the politics of looking. By making the viewer highly aware of their own act of looking, the image acknowledges both the power structure, giving it credit, and the disruption, which is only possible because of the power relationship. The Afghan girl’s resistance through her gaze has the function of reinvesting power and redistributing it among the discourses which naturalize her position.

Throughout these readings of the image, Scarry’s work allows us to think about the way this photograph and its proliferation in Western society performs like torture and like pain. Where Said states that the “actual” Orient has been displaced by “unshakable abstract maxims,” Scarry’s work applies the similar idea about analogical verification (Said 52). Pain is not pain in and of itself; it can only be understood through a referent. Like pain, a photograph has a direct link to its referent. The characteristics of a photograph, its indexical properties, what the viewer “knows” because of it, are displaced away from the subject of the image. Scarry helps reading these images by offering a theory of power and agency that applies to the production of images. These images, while being of the body, create spaces that remove it; the danger lies in “the ease with which it can then be spatially separated from the body” (Scarry 17). The power of torture lies in its ability to separate the person in pain from whom or what inflicts pain. Images are planes (paper, canvas) of separation in time and space which polarize the viewer and the viewed.

This image’s popularity and place as one of the most iconic photographs of the late twentieth century illustrates the West’s continued fascination with the Oriental Other. In comparison to Delacroix’s painting and Sevruguin’s image, the viewer is even closer to this subject. She is closed off from all but one cultural and civilizing signifier: her head-cloth. If the veiled woman is a source of extreme visual frustration for the Western Male gaze, this image, while not visually frustrating in the same way, lends the possibility that she could at any moment pull the cloth over her face. The image is a portrait, cropped so closely that she is only left with the cloth and once again appeases the Western perception of the female other as controllable. Had McCurry chosen to widen the angle or include objects of her surroundings, her gaze would have been less unique and she would have been given contextualization that would show her as a member of greater human civilization. Even if this removal of cultural signifiers allows her to transcend certain boundaries, it does not change the fact that the image is received by a Western audience whose mindset demarcates the Eastern Other as separate and inherently different. The green eyes invoke an element of sameness (whiteness); the cues of her veil and hair color depict difference. The color “incongruities” matter because racial difference has a history of being used to discriminate in order to keep the Self separate from the Other. By confusing what the viewer “knows” about the colors of the non-Western Other, the girl’s eyes draw attention to that discourse. The West has repeatedly used racial difference to justify violent actions. Scarry’s assertion that the torturer enlarges their own world at the expense of the prisoner’s reflects the West’s preoccupation with diminishing and removing any threat to its superiority.

Western audiences, obviously fascinated with the expression captured in this photograph, require the fascination to be aesthetic and, if confrontational, controlled. The framing (and the caption) reasserts Western agency even as she confronts the viewer. The duplication of this photograph, her flattening and objectification, turns her into a consumable work of art. Because the viewer continues to consume this image and subscribe to these ideologies, her agency is diminished. Her gazing back is ultimately reduced by the fact that the she is framed by the Western eye (eyes), enabling viewers to make assumptions which reaffirm their position of power.

The creation of these three images marks the West’s desire to remain the keeper of power over the Eastern Other. Though examples of different circumstances each image demonstrates the Orientalist viewpoint, a way of looking at the East/West relationship as a binary that has been maintained even in a post-colonial world. The West continues to define its Other through images like the Afghan Girl which divide the world into manageable items of consumption. Orientalism as both an art genre and a frame of mind depicts a relationship of the powerful over the powerless that effectively manipulates the Other in order to deny agency and uphold a notion of power that accompanies this kind of representation. While I cannot propose that there is or can be such a thing as a neutral image, because as viewers we do not come from neutral points of view, it may not be impossible to alter power structures at some point in the future because these images, each in their own way, attempt to disrupt the West’s historical monopoly on power. I find them unsuccessful now not because they lack some degree of agency, but because they are created in and maintained by the Western viewer who will not easily submit the self to the subjugation that has been delved to the Eastern Other.

References

Behdad, Ali. “Sevrguin: Orientalist or Orienteur?” Sevruguin and the Persian Image. Ed. Frederick N. Bohrer. Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1999. pp. 79-97. Print.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Company and Penguin Books. 1972. Print.

Blocker, Jane. Seeing Witness: Visuality and the Ethics of Testimony.. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2009. Print.

Bohrer, Frederick N. “Looking Through Photographs: Sevruguin and the Persian Image.” Sevruguin and the Persian Image. Ed. Frederick N. Bohrer. Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1999. 33-53. Print.

Djebar, Assia. “Forbidden Gaze, Severed Sound.” Women of Algiers in Their Apartment. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992. pps. 133-151. Print.

Fanon, Frantz. “Algeria Unveiled.” A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press, 1956. pps. 35-67. Print.

Houghton, Walter Edwards. The Victorian Frame of Mind, 1830-1870. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1957. Print.

Lutz, Catherine A. and Jane L. Collins. Reading National Geographic. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press. 1993. Print.

Mora, Stephanie. Delacroix’s Art Theory and His Definition of Classicism. Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Spring 2000), University of Illinois Press. pp 57-75. Web. 29 Oct. 2009.

Oxford English Dictionary Online. “Gaze.” <ww.oed.com> Ed. 1989. Accessed 10/3/07.

Porter, Laurence M. “Space as Metaphor in Delacroix.” The Journal of Aesthetics and

Art Criticism, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Autumn 1983). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 29-37. Web. 29 Oct. 2009

Said, Edward W. “Imaginative Geography and Its Representations: Orientalizing the Oriental.” Orientalism. New York: Random House, 1979. pps. 49-73. Print.

Scarry, Elaine. The Body In Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Print.

Sheikh, Reza. “Portfolio of a Nation.” Sevruguin and the Persian Image. Ed. Frederick N. Bohrer. Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1999. pp. 55-57. Print.

Snow, Edward. “Theorizing the Male Gaze: Some Problems.” Representations. No. 25. (Winter, 1989): pp. 30-41. Web. 30 Nov. 2009.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Picador. 1977. Print.

Stein, Donna. “Three Photographic Traditions in Nineteenth Century Iran.” Symposium: “The

Art and Culture of Qajar Iran.” New York: April 4, 1987. PDF file.

Vuurman, Corien J. M. and Theo H. Martens. “Early Photography in Iran and the Career of Antoin Sevruguin.” Sevruguin and the Persian Image. Ed. Frederick N. Bohrer. Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1999. pp. 15-31. Print.