Saint or

Sinner?

My understanding and appreciation of the life style of the Indians

of Southern California prior to the arrival of the Spanish explorers and clergy has

increased during the past fifty plus years of association with their descendants and

research of the records left by the explorers and pioneers.

Each of the various Indian peoples of Southern California contacted by the explorers,

clergy, and pioneers had the same basic needs as do all people throughout the world today,

and these same basic needs have been experienced by all people throughout all time periods

in the history of people. These basic needs include, but are not limited to, the need to

relate to the universe, the need for food, the need' to procreate, the need to belong to

and to be a part of a group, the need to love and be loved, the need for artistic

expression, the need to communicate, the need for shelter and clothing, and of course all

people have the same body function needs.

That they were able to meet their basic needs and not

only survive but multiply in diverse and often harsh environments, indicates that the

early Indians of Southern California had intelligence, strength, endurance, resilience and

adaptability.

That they were able to meet their basic needs and not

only survive but multiply in diverse and often harsh environments, indicates that the

early Indians of Southern California had intelligence, strength, endurance, resilience and

adaptability.

The Southern California Indians met their need for food by using more than sixty

varieties of native plants for nutrition and probably an additional thirty for stimulants

or medicines. A great many animals and even some insects were also utilized as food. No

one had a monopoly on the food resources, and each individual participated in the

procurement and preparation of the plant and animal resources for meeting the basic human

need for food.

All people from the beginning of time to the present have searched for and developed a

relationship with the universe. People have sought a source of power greater than their

own. Both the methods of the search and the resulting beliefs or doctrines have been

diverse, but also there have been some similarities among all people in respect to the

great fundamental universal truths which nurture the continuation of the human species.

The Indians of Southern California, long before the arrival of the Spanish, had

developed cosmological concepts, value systems, a moiety system that regulated marriage,

and a cyclic food gathering system that supported an increasing population in apparently

reasonably good health. They had developed skills in providing necessary clothing and

shelter, and even among some populations practiced agriculture somewhat similar to that

practiced by the ancient Egyptians. Their communication skills we're adequate to meet

their needs, and their need for artistic expression was manifested in a variety of ways

during their daily activities.

In May, 1769, Don Miguel Costanso, who compiled the narrative of the Portola

Expedition, described the Indians of the San Diego area as being "well-built,

healthy, and active." Fr. Serra on July 3, 1769, wrote that the Indians of the San

Diego area were exceedingly numerous, lived well on various seeds and on fish obtained

from the sea, and that they were very friendly. Costanso made further comment about the

Indians while on the journey up the coast with Portola's party. He stated that the whole

country was inhabited by a large number of Indians who were very docile and tractable. Fr.

Crespi, in August, 1769, wrote of the Indians bringing abundant presents of seeds, acorns,

and pine-nuts for Portola's party.

Fr. Garces, a devoted priest and early explorer, described the Indians as being strong,

healthy, friendly, generous in sharing their food with him, and helpful in guiding him

across the desert. Garces was well treated by the many Indian groups he visited during his

two thousand mile journey over desert, mountain, and river lands in the southwest. He

wrote of the Mojaves along the Colorado River as being very superior and of taking

excellent care of him.

Descriptive terms of "great fishermen," "ingenious," "well

built," "good disposition," "agile," "alert,"

"diligent," "skillful," "peaceful," and "great

hunters" appear throughout the written accounts of the earliest explorers.

The decimation of the Indian population of Southern California began during the mission

period of California history and has been well documented. There were many causes for the

rapid decline, with perhaps health, nutrition and pressure from the aggressive

Spanish-Mexican culture being the most critical.

King Carlos III of Spain became alarmed upon learning of the Russian fur traders'

exploration and occupation of California north of San Francisco. Efforts to proceed with a

Spanish plan to colonize California resulted in what was termed a "Sacred

Expedition" composed of two divisions. The military division was under the command of

Captain Don Gasper de Portola, and the Roman Catholic Church division was under the

command of Father Junipero Serra. Spanish ships loaded with supplies were sent to meet and

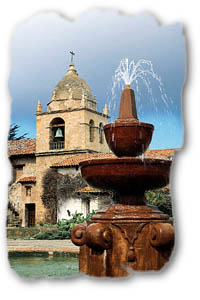

supply the "Sacred Expedition" at San Diego. Here in 1769 the first of a series

of missions reaching from San Diego to San Francisco was established. Mission San Gabriel,

the fourth of the series, was established near Los Angeles in the San Gabriel Valley in

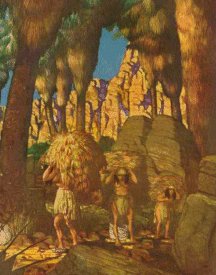

1771. The local Indians assisted in cutting the timbers, dragging the logs to the mission

site, and helping with the construction. The Indians of Southern California shared their

friendship and their food resources with the members of the "Sacred Expedition" who had been sent by the Spanish authorities to impose on all California Indians the rules

proposed as early as 1519 by the Franciscan bishop Rt. Rev. Juan de Quevedo, and practiced

at the Franciscan missions in Texas and Mexico. The essential features of these rules have

become known as the Mission System.

The Mission System, as viewed by some of the Indians, meant not

only a complete change in the way they had learned to meet their basic needs, but absolute

slavery to an established hierarchy in all matters spiritual and temporal. Their previous

life style had provided more individual freedom.

The Mission System, as viewed by some of the Indians, meant not

only a complete change in the way they had learned to meet their basic needs, but absolute

slavery to an established hierarchy in all matters spiritual and temporal. Their previous

life style had provided more individual freedom.

The missionaries, according to Fr. Zephyrin Engelhardt, believed they had "encountered a race of people who did not reason, whose thoughts turned on nothing

higher than how to fill their stomachs without laboring to produce that which would

sustain life." The missionaries, because of a great communication gap due not only to

the language barrier, but also to the cultural barrier, believed it useless to begin the

work of converting the Indians to their religious beliefs by reasoning. They believed the

Indians had no idea of the creator and neither knew nor cared where they came from or

where they would go. So they treated the Indians as little children giving them presents

of trifles and food at first for any service rendered. The treatment in fact made the

Indians beggars, dependent upon the missionaries who were supported by military force.

The women and girls were soon collected and placed under a matron, and the men and boys

were used as laborers to farm the lands after the oak trees that had provided them with

food were cut and used as lumber to build the mission buildings. Those who could not

comply with the restrictions and ran away were pursued, captured and returned to the

mission for punishment. In fact some reports would indicate that expeditions were sent out

from the mission to capture the women and girls of Indian villages, knowing that the men

and boys would follow the expedition back to the mission to try to stay close to their

family members.

An early unfortunate event occurred at San Gabriel Mission soon after it was founded

that illustrates not only the lack of communication between the Indians and the Spanish

but also gives one example of the cruel punishment inflicted upon the Indians to induce

fear and thus compliance with the wishes of both the military and spiritual authorities.

One of the soldiers raped the wife of the chief of the village, and the chief, wanting to

punish the soldier, gathered some friends and with their bows and arrows attempted to get

close enough to release their arrows and inflict harm to the soldier. The soldier had a

leather jacket for protection from the arrows and used his gun to shoot the chief.

The shot frightened the Indians, who fled. It also alerted the other soldiers at the

mission who came and helped cut off the dead chief's head. This was placed on a pole which

was then taken to the Indian Rancheria to further frighten the Indians into submission.

Within a few days some of the Indians came to the mission and asked the missionary for the

head of the chief, which he gave to them. The fact that the soldiers who accompanied the

missionaries abused and mistreated the Indians was a constant problem and at times created

conflict between the church authorities and the military authorities.

Missionaries also inflicted punishments. Usually shackles, the lash and the stocks were

used when Indians failed to understand the obligations placed on them by the missionaries.

Such punishments were usually considered to be much like what a parent at that period of

time could use on his own children. The Indians who could not or would not conform to the

Mission System had the alternatives of fleeing from the missionaries or dying. At the San

Gabriel Mission the baptismal register for 1794 listed 2,552 baptisms and 1,181 deaths,

and in 1845, a total of 8,841 baptisms and 6,048 deaths. These records verify that there

were many who died.

On May 20, 1810, the venerable Franciscan Mission Priest Francisco Dumetz of the San

Gabriel Mission led a company of priests, soldiers and neophytes into the San Bernardino

Valley and conducted the first Christian worship among the Indian residents and others who

were gathered to observe the feast day of St. Bernardine of Siena. Accordingly, the priest

named the valley San Bernardino, a designation which later applied to the nearby mountain

range, a particular mountain, and eventually to both county and city.

The authorities of San Gabriel Mission wished to extend their influence over the

Indians of the San Bernardino mountains, the inland valleys, and the desert areas and

proceeded to establish an Asistencia, or branch of the San Gabriel Mission, in the San

Bernardino valley. An irrigation ditch was completed by the valley Indians under the

supervision of a Spanish majordomo in time for a planting of crops in 1820. More than

1,000 Indians responded to the mission invitation and many assisted with the necessary

work. A year later there were about 200 Indians still around the mission branch at San

Bernardino, and most of these had been baptized at the San Gabriel Mission.

Descendants of the San Bernardino Valley Indians have indicated that their people

became unhappy with the mission authorities because the food produced was taken to the San

Gabriel Mission, and they did not receive what they considered a proper share of the food

grown. This discontent continued and later led to hostility between the Indians and

authorities from the San Gabriel Mission.

The Mission System, as well as contact with the military personnel and settlers brought

from Mexico to occupy-the land, began the destruction of the Southern California Indians'

spiritual and economic way of life. This decline, not only of the "life style",

but of the Indian population, was accelerated after Mexico won its independence from

Spain, initiated the secularization decrees, and the missionaries were recalled from their

work in California.

The Spanish impact on the culture of the Indians of Southern California was not unique.

The history of all people throughout the world reflects cultural change because of contact

with other people. The Spanish mission system impact came quickly upon the Indians and was

harsh, demanding and unrelenting. Those who survived best and kept some of their old

culture were the larger population groups more distant from the mission locations and

therefore less affected by the destructive influences.

Rupert Costo, a Cahuilla descendant of one of the groups less affected by the

Spanish mission system, was very much opposed to the plan of making Rev. Junipera Serra a

candidate for sainthood. Serra, a Spanish priest who died in 1784, was a pivotal force in

California's early history. After arriving in 1768 in what was San Diego, he directed a

group of Franciscan priests who established a chain of nine religious missions to convert

California Indians to Catholicism and made plans for eleven others which were completed

after his death.

Rupert Costo, a Cahuilla descendant of one of the groups less affected by the

Spanish mission system, was very much opposed to the plan of making Rev. Junipera Serra a

candidate for sainthood. Serra, a Spanish priest who died in 1784, was a pivotal force in

California's early history. After arriving in 1768 in what was San Diego, he directed a

group of Franciscan priests who established a chain of nine religious missions to convert

California Indians to Catholicism and made plans for eleven others which were completed

after his death.

Rupert Costo was among those who attended a conference in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1987,

where Pope John Paul II participated in a special event in his honor. After stating that

the time had come to go forward, forget past mistakes and work for the future, the pontiff

stated:

"One priest who deserves special mention among the missionaries is the beloved

Fray Junipero Serra, who traveled through Lower and Upper California. He had frequent

clashes with the civil authorities over the treatment of Indians. In 1773 he presented to

the Viceroy in Mexico City a Representacion, which is sometimes called a 'Bill of Rights'

for Indians. The Church had long been convinced of the need to protect them from

exploitation. Already in 1537, my predecessor Pope Paul III proclaimed the dignity and

rights of the native peoples of the Americas by insisting that they not be deprived of

their freedom or the possession of their property. (Pastoral Officium, May 29, 1537: DS

1495). In Spain the Dominican priest, Francisco de Vitoria, became the staunch advocate of

the rights of the Indians and formulated the basis for international law regarding the

rights of peoples..."

Rupert Costo took exception to these remarks because he believed Pope John Paul was

misinformed. Rupert stated that it was not Serra who presented the so-called Bill of

Indian Rights to the Viceroy of Mexico. It was Captain Juan Bautista de Anza. Serra had

agreed, but then proceeded to violate every point in the document.

It was in the same 16th century when Pope Paul III proclaimed the dignity and rights of

the native peoples of the Americas that Cortes committed genocide against the Mexican

Indians, stealing their gold to send to Spain and confiscating their properties. Rupert

Costo believed John Paul II was truly misinformed when he spoke in Arizona and had not

examined extensive evidence which had been presented regarding the California missions'

genocide against the Indians.

The Spanish mission period of California history only lasted for about -fifty years and

was followed by the Mexican Rancho period of twenty-five years before California became a

part of the United States.