|

The MIAO-TZE

Paper written for the Fortnightly Club, Redlands, California

November 30, 1972

Frank M. Toothaker

From the high, barren plateaus of outer Mongolia toward the northern outreaches of the Himalayas the 4,000,000 square miles of China’s land mass sweeps southward and eastward toward the Pacific Ocean. The largest province, Sinkiang, sprawls in the northwest corner, much of it a plateau at 10,000 feet above the sea level. It offers wide spaces, but not much more.

Two prodigious river systems follow the eastward continental tip until they empty into the Pacific. The Huang-Ho, or Yellow river has rampaged with unimaginable floods, whence its other name, “ China’s Sorrow”. It carries vast quantities of loess silt. From the days of the early emperor Kao Yao down to the years of the faltering Empress Dowager, who once retained Herbert Hoover to conquer it, the Yellow River has wrought death and destruction. Its outflow colors the entire China sea.

The Yangtse-kiang, fifth river in the world in length lends its 3400 miles of usable waterways to reward its nation. For transportation and travel it has been her most dependable workhorse. Even today, with modern railways networking China’s cities and tapping sources of raw and finished materials this wide waterway, deep enough for ocean carriers, links the seaport of Shanghai with the key steel centers of the Hanyang cities far inland.

Within this far flung panorama, most of it lying under a stimulating sun, in a temperate zone, stretch the vast food producing plains, the rice bowl of 650,000,000 people, the sons of Han. In pride they call their nation “chung kuo”, the central state of states. A western scholar, Dr. Williams wrote of China as “the Middle Kingdom”. Clearly, the Sons of Han think highly of themselves. Many years after the early dawn of Chinese civilization Marco Polo agreed that their splendors indeed were surpassing, and his reports to Europe at first were laughed to scorn. Marco Polo was a late comer who knew little about who these Chinese were and whence they came.

Anthropologists generally suggest that the Han Chinese drew out of the wandering nomads in the northwesterly highlands. They admit that some influences may have infiltrated northward across Szechuan from Thibet. The Han drifted down into what now is the province of Shensi, the general area in which the Communists early found shelter. Perhaps they simply tired of wandering and began to settle into an agricultural society. New ways of living and a better diet encouraged more rapid multiplication of people. All this took place in China’s prehistoric era four thousand years B.C. The first two thousand years of legendary history produced its folk-tales, but little more substantial. Still, we must not miss the fact that miraculous changes took place, and that these changes spell the difference between the estate of the roving tribes and the amazing civilization that breaks upon us, evidenced by prized artifacts and scraps of written history. The mythical years were a period of achievement.

So the Sons of Han, possessed initiative, curiosity and persistence. They also multiplied and required more living room. Like Abraham’s tribe bound for the Promised Land they did not move into an empty place. They found people but not an invitation to move in. The infiltrators met opposition. The confrontation could not be bloodless. It mattered not that the aborigines and the Han Chinese doubtless had arisen from the same anthropological stock, classified as Austro-asiatic or Mon-khmer. The Chinese looked upon the aborigines as not more than half human. Such is the stuff of which massacres are made.

We have to ask: Why did the pre-historic Chinese surpass their competitors? In physical vigor they cannot claim to have been ahead. They praised their thinkers and gave them power. They learned how to produce better materials for food and utility. They planted grains, which with leafy vegetables and game, or domestic animals took care of the food problem. An early day empress is credited with domesticating the silk worm and of inventing the skills of weaving. The Han Chinese produced an engineer who later became the emperor. Yü ended a ruinous thirteen year long flood in the Yellow river valley. His predecessors had tried to curb the waters with dikes, and had failed. Yü deepened the main channel, probably the best that could have been done with hoes and bamboo baskets. The common people celebrated shouting: “Were it not for Yü we would all have been fish”.

The aborigines, including the Miao-tze apparently lacked some of the characteristics of growth and power. Of course they did what they could to repel the spreading Chinese population. The Book of History recounts the story of Yü’s battle against the river, and the charge that the Miao refused to help. Here is his report to Emperor Kao Yao:

The Emperor said, “Come Yü!

You must have admirable words for me”.

Yü did obeisance, and said,

O Emperor, what can I say?

I can only think

Of maintaining a daily assiduity.”

Kao Yao said, “Alas! Will you describe it?”

Yü said: “The inundating waters seemed to assail the heavens,

With roar and rush they embraced the mountains

And overtopped the hills;

So that the multitudes in the hollows

Were bewildered and overwhelmed.

But I forced ways through for myself

And hewed down the woods all along the hills;

I showed the people how to get flesh to eat.

I opened passages for the nine streams,

And conducted them to the four seas;

I deepened the channels and led them to the streams,

I showed the people how to procure

In addition to meat the food of toil. [grain]

I urged them to make an exchange of goods;

Deficiency and excess were remedied.

In this way all the people had food,

And all the states began to acquire good rule” …

Yü said: “From T’u Shan I took me a wife,

But I stayed with her only four days.

On my return I paid no heed to the wailing of my son;

My thoughts and planning were all in my work.

The provinces demarcated by me

Extended far and wide:

To every one a pastor I gave;

Their rule extended to the seas.

The tutors appointed by me throughout

Proved worthy of their task.

Alone the obdurate people of Miao

Refused their duty to fulfill.

O Emperor ponder this.”

The under-skilled and outnumbered non-Chinese had two options. One was to abandon the more desirable areas and crowd into remote, forested, rocky highlands. Or, they could retreat south or southwesterly away from the new squatters. Some took one option, some took the other. Not infrequently blood flowed, the tribes attacking the infiltrators with poisoned stone axes and poisoned arrows. The main story, however, recounts the retreat of the Miao-tze and their fellow aborigines.

Why did they choose either of these ways of meeting the Han-Chinese? They refused to consider intermingling. They would have none of intermarriage. As adamant they determined to maintain their group identity. They loved their inherited language, and denied any move to let it become a polyglot. To gain these two values they saw no other method than to set up a separated and isolated communal existence. This they did and until today they still do. We shall not try to judge whether the game was worth the candle.

Their success, if such it can be called, brought further suffering upon them. From the outset they had been made victims of such indignities as a self-styled superior race heaps upon others. The name “Miao-tze” itself may be an epithet, meaning “Children of the soil”. Another aboriginal tribe is called the “Hakka”, the inferior guests. Added to these tribal designations may be a whole potful of names – dogs, wild men, barbarians, savages, all seemed to have current use. Even in the day when the Empire crumbled under its rot and weight the Nationalists found no place to honor these peoples whose origin is hidden in the mist of the ages. The Nationalist flag noted five racial groups, Chinese, Mongol, Manchu, Moslem and Thibetan – but no place for the 6% of the tribes of which we write.

Governmentally, how had the Miao-tze fared? The Empire had tried to ignore them. The Nationalists slurred over their condition, trying no more than to maintain a semblance of control through officials called T’u ssu, strictly local level head-men. The People’s Republic has been developing a changed attitude, frowning on insults while taking steps to diminish the chasms of separation now so deeply traditional. Potential progress for these tribesmen is assumed to be better sought within their own traditions, rather than through coercion. Let them preserve their time toughened cultures but try to involve them in closer association with communist social and economic living. Be sure, however, that no overt rebellion will be allowed, any more than it was in Thibet.

We have spent perhaps too much time on historic trends, but how otherwise find the answer to: “Whence came the Miao-tze?” Even at that, it is like asking “whence the human race?” To the Hebrew-Christian tradition Genesis makes reply. But then, there were the Greco-Roman myths, and the Nordic myths, not to mention others. Dr. D.C. Graham, a West China college faculty member developed friendly relations with the Chüan Miao until they sang their songs and recounted for him their stories. With the help of a Miao speaking Chinese interpreter he gathered hundreds of these bits of insight and the Smithsonian Institution has published them among their miscellaneous collections. I asked, “Whence came the Miao-Tze?” Here are two of these legendary answers as told in my own words:

There were two original persons, a man and a woman.

They were brother and sister. They had no home.

They burned down trees, cleared land, planted rice, and made for themselves a home.

They married each other and had a family.

This was the beginning of the Miao.

Another myth goes this way:

There was a beautiful virgin.

She went bathing in a deep pool of cloudy water.

While swimming she felt a thrust, but saw nothing.

Afterward she was found to be pregnant.

She had been impregnated by the water dragon king.

She bore a son who became the progenitor of the Miao.

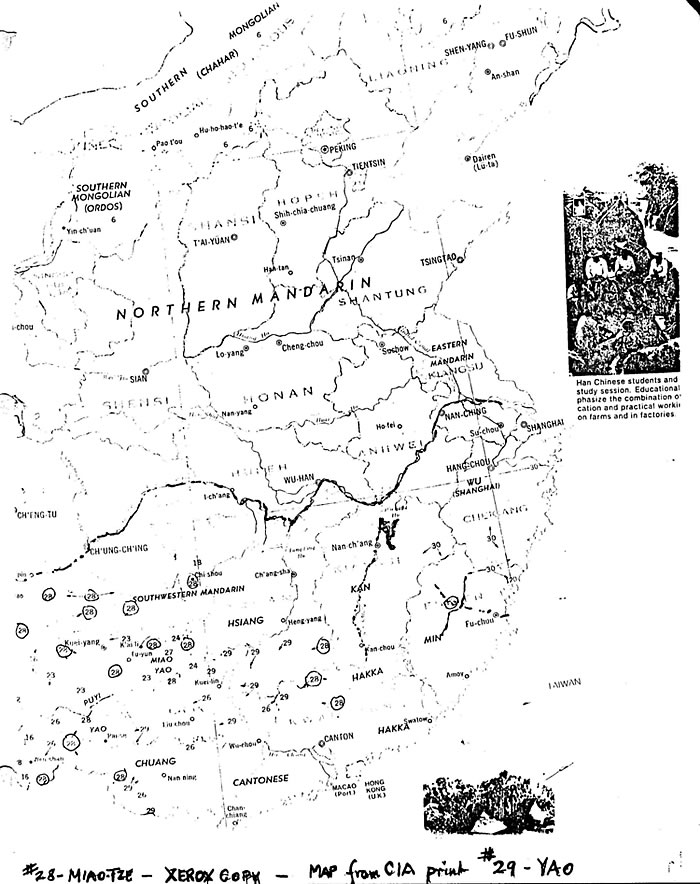

Whatever their origin, the Miao-tze became a stubborn, interrelated network of at least eighty-two identifiable tribes, scattered over western China, and south to the Himalayas, and in the southern provinces, east to the Pacific. The Island of Hainan, 100% Miao has a story. The government was plagued by a revolt of the Li tribe. To put down the Li an army of the Miao-tze was sent in. The Miao-tze did what they were sent for, but they never returned control of Hai-nan to the Empire. Further, it appears that elements of the Meo (or Miao) are currently resident in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

The one village of the Miao-tze known to me is a hillgirt, forested fastness in Fukien province above the valley of the Min river. Christian missions of Anglican, Congregational, Methodist and Roman Catholic were carrying on a widely varied program of services in the general region, but none of the agencies ever penetrated the Miao-tze settlement. It would not be just to suggest lack of concern for these people. I knew of no one who could speak the Miao dialect. Hospitals, schools, churches, social agencies were open and inviting to all, but none of the Miao-tze ever came for any help. Our local missions were so overwhelmed by the vast needs of the Chinese that I presume we concluded we were as extended as we dared be. In other places, Yunnan province for example, the English Methodists began work among the Miao as early as 1880. In all of China, as far as I can discover there exists no printed literature in the Miao dialect.

The Fukien Miao-tze may be described as lithe and sinewy, and never fat, well built but not brawny. The men do not stand tall like the Peking Chinese, or the Lolo tribesmen of Thibet. In stature they remind us of the older generation Japanese. I suppose they would be called members of the yellow race, but they are deeply bronzed of skin. Round black eyes look out of round faces, with noses and mouths suitably proportioned and undistinguished in shape or size. Men keep a thatch of scotched black hair, and if they ever have beards I never noticed. Women put their hair up in a big doughnut-shaped roll completely circling the head. Fukienese Miao-tze build up a knot on top of their head. Into the knot in a complete circle they thrust long pins. The outer end of the pins bear curiously wrought coin shapes, in size approximately as large as a half dollar. All of the women delight in beads, even when dressed in their ordinary work costumes. One novelty distinguishing one tribe from another is the women’s habits of color styles. Thus we have the Red Miao, the Blue, the Black, the White and the Flowery.

Imagine that we have taken some vantage point along the roadside to scout the traffic. We have chosen one of the Tenth Days of the Lunar month, which in larger market towns is the big day of trading. A single file of load-bearing Miao-tze approach, all clad in native indigo dyed clothing. Hair ornamentation and beads distinguish the women. They carry about the same loads. Each crosses the shoulders with a “dang-dang stick”, a springy shaped bamboo. Each bearer half jogs, half walks, keeping such careful rhythm to the up and down spring of his stick. Bundles of kitchen firewood hang from some sticks. Other carriers have bales of dried, edible bamboo shoots, or woven bamboo bags of unhulled rice. One may have a couple of pigs, each in a carrying sling. A load of charcoal would not be unusual. Whatever the product may be it provides trade goods for the local tribe.

When the day has worn past noon, or the goods have all been traded the caravan turns homeward. Most carry nothing on their sticks except the ropes that previously attached their loads. Now, returning, some will have a bamboo joint of oil, or a new cast iron cooking pan. Perhaps one pole will dangle a heavy backed, blunt ended machete to be used as an ax. There may be a parcel of blue cloth or a package of cheap bowls wrapped in brown paper tied with rice straws. The market day took the Miao-tze into town, but their use of the Chinese language or of the coinage of exchange seemed to them not an opportunity but of a necessity. Up on the hill stands the hospital. They may have asked, “What is that?” but they went no further. They passed a school where Chinese youngsters became literate at the top of their voices. Perhaps a load-bearer stopped to rest and listen, but he did not inquire, “Could my son go there?”

Here are the elements of tragedy. The Miao dialect is not so different from Chinese. It is monosyllabic. Word meanings require tonal distinctions. There are no inflections, conjugations and no gender. Obviously it is a tool for expressing meaning, probably comparable in awkwardness to the Mandarin.

So language does not account for what I cannot but call tragedy. Neither does the tribal determinations to reject intermarriage with outside peoples. In the main the Miao family is patrilinear and monogamous. At this point we recall another small tribe of the followers of Abraham who jealously guarded their marriage habits.

The tragedy in the tightly knotted, inturned Miao society developed because across some thirty centuries they did not encourage authors, writers, experimenters, painters or even whittlers. Others held out honor for the calligrapher, or the wood carver, or the potter, but not the Miao-tze. Prizes went to Chinese devotees of learning and art, and with the prizes went position and power. Somehow the Miao-tze missed this trick. While China was cultivating an elite whose authorship filled vast libraries of religion, poetry, fiction and history, the Miao-tze just kept a living on. For them no incomparable wonder such as the Temple of Heaven or the beauty spots of Soochow and Hangchow. Since we mentioned the Hebrews a moment ago we must add that the Miao-tze gave the world no law-givers like Moses, no prophets like Isaiah and no songwriters like David. This adds up to what I have called tragedy.

The Miao-tze now live under a revolutionary regime. It will be interesting to someone to discover what this new regime can do, within the coming century, to rescue two and one half millions of sturdy people. They may not have been given ten talents, but such as they were given they have, until now, buried wrapped in a napkin.

Let me close this sketch by sharing a sample of their songs and stories. Here we taste the wine of their joys and sorrows. Here we sense their indignation over wrongs suffered and their praise of justice done. Here stir the tempers of their souls. Here truth wrestles with deception and honor fences with cupidity. Here brotherhood falls victim to racism. One sort of loyalty to the tribe may be shown to be disloyalty to greater goals. Life and death ride in the same boat. Sex and celebration involve the spirits of the invisible world. Yes, they live always in the world of spirits, good and evil. How throbbingly human are these songs. They live, I am sure, because at evening time, when the candle gutters, what child does not ask: “Grandpa, tell us a story.”

“The Tiger and the Toad”, sung by Mr. Yang Han Ch’in.

Jin Dang and Jin Nang were two men whose families had intermarried. Once one went to visit the other in his home, and the other went to kill a chicken so as to give him a feast. The mother hen said, “I can lay eggs. You should not kill me.” Therefore he went to kill a rooster, and the rooster said, “I am efficient in crowing. You should not kill me.” He therefore did not kill the rooster, and went to kill a goose. The goose said, “You should not kill me. When thieves come I cry out and awaken you.” He then went to kill a rabbit, and the rabbit said, “I only eat grass and do not eat your meat. You should not kill me.”

The goose ran to the toad, and the toad asked, “Why do you run?” The goose replied, “My master wants to kill me.” The toad asked, “Why does your master want to kill you?” The goose said, “The two intermarried families want to have a good time.” The toad said, “Does he want to kill me?” The master said, “You will do.”

The toad therefore fled and met a tiger. The tiger said, “Mr. Toad, why do you run?” The toad said, “Because the master wants to kill me.” The tiger asked, “Does he want to kill me?” The man said, “You are truly fierce, so I want to kill you.” The toad and the tiger then consulted. They said, “We will see which can run the fastest?” The slowest would be killed.

The toad thought of a plan and bit the tail of the tiger. The tiger fled fast, and the toad held onto the tail of the tiger. The tiger switched his tail, and the toad was thrown in front. The tiger then cried, “Mr. Toad here I am. How can you run so rapidly?” The toad said, “I leap quicker each time than you can jump.” The tiger said, “Should I learn to run from you?” The toad said, “If you want to learn from me how to run, you should change your fierce character, and you will have learned from me.” The man, seeing the good trend, did not kill either of them.

Now in conclusion, here is the song about the Chinese who deceived a Miao who could not read.

Once there was a Miao who was very poor. He hired out by the year to a Chinese. They first agreed that every year he would be paid a cow. The Miao did not trust the Chinese, so the Chinese wrote an agreement and gave it to him. Then the Miao worked for the Chinese ten years.

One day the Miao reckoned accounts with the Chinese. He had worked for the Chinese ten years. The Chinese railed at him and said, “I did not agree to give you a cow every year.” The Miao said, “Did I help you herd your cattle?” Then they quarreled fiercely for several days. The Miao then said, “Your written agreement is still here. You quickly give me ten cattle.” Then the Chinese beat him a while and took him to the local headman.

The Miao was not efficient in talking and only said, “There is a written agreement. It can serve as evidence.” But on the paper it was written that each year he should be given a pound of oil. Then the headman decided thus, and the Miao could only cry and accept his ten pounds of oil.

But the Miao from this time told the rest of the Miao not to go and work for the Chinese, but just make clearings for themselves. In this way the Miao gradually became industrious and gradually had food enough to eat, and their descendents are all farmers and do not dare to work for the Chinese for wages.

After the Miao left the Chinese had nobody to work for him, and his family daily became poorer. Later the Chinese had to sell his children to get food to eat. The Miao was glad, and said, “The Chinese sold his sons as slaves to others and sold his daughters as harlots.” So the sufferings of us Miao people have been advantageous. Is it not well then for me to leave this song (for later generations to sing and hear).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baber, E. Claborne. “Travels and Researches.” Royal Asiatic Society Papers, 1882.

Boulger, Demetrius C. “Short History of China.” 1900 edition.

Bridgman, E. C. “Sketches of the Miao.”

Buxton, L. H. D. “The Peoples of Asia.”

Edkins, Joseph. “The Miao-tze.” 1870 (not obtained, perhaps out of print).

Graham, D. C. “Songs and Stories of the Ch’uan Miao.” Smithsonian Institution Papers, 1954.

Henry, B. C. “Ling Nam.”

Hudspeth, W. H. “Stone Gateway and the Flowery Miao.” 1937.

Kirby, E. S. “Contemporary China”. 4 vol. 1958-1960.

Li Ung Bing, “History of China”. 1913.

Wilhelm, Richard, “History of Chinese Civilization.” 1929.

Encyclopedia Americana, Vol. 19.

National Geographic, March 1971. “The Lands and Peoples of Southeast Asia.”

|